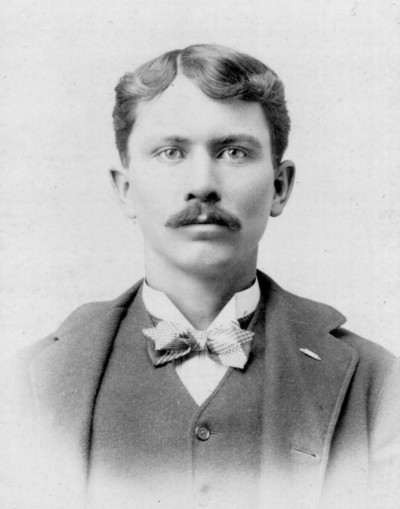

Thomas Horn (Tom Horn)

Known as “Tom,” he was born in 1860 to Thomas S. Horn, Sr. and Mary Ann Maricha (née Miller) on their family farm in rural northeastern Scotland County, Missouri. They had 600 acres (bisected by the South Wyaconda River), located between the towns of Granger and Etna. Tom was the fifth of twelve children. During his childhood, the young Tom suffered physical abuse from his father. His only companion was a dog named Shedrick, which was sadly killed when Tom got into a fight with two boys, who proceeded to beat Tom and killed the dog with a shotgun. Horn wandered and took jobs as a prospector, cowboy and rodeo contestant. Horn allegedly killed his first man in a duel — the man was a second lieutenant in the Mexican Army. Horn, at age twenty-six, killed him as a result of a dispute with a prostitute.

At sixteen, Horn headed to the American Southwest, where he was hired by the U.S. Cavalry as a civilian scout under Al Sieber. He served during the Apache Wars, aiding in the capture of warriors such as Geronimo. On January 11, 1886, he was involved as a packer and interpreter in an expedition into Mexican territory in the pursuit of Geronimo. While crossing the Cibicue Creek, Sieber together with Horn, another civilian named Mickey Free and the army were ambushed by the Apaches. Prior to the ambush, Horn and Free knew of the attack and tried to warn their officer Captain Edmund Hentig but was rebuked in return. During the ambush, Sieber ordered the two scouts to return fire from a hill, and together with the soldiers, managed to repel the ambush. Tom Horn and Al Sieber also participated during the Battle of Big Dry Wash, where he and Lt. George H. Morgan slipped to the banks opposite of the Apache line, and provided fire for the battalion. During the operation, Horn’s camp was also attacked by Mexican militia, and he was wounded in the arm. Horn was present at Geronimo’s final surrender, and acted as an interpreter under Charles B. Gatewood.

In his line of work, Horn developed his own means to fight cattle-rustling. Horn described his action when he encountered rustlers: “I would simply take the calf and such things as that stopped the stealing. I had more faith in getting the calf than in courts.” If he thought a man was guilty of stealing cattle and had been fairly warned, Horn said that he would shoot the thief and would not feel “one shred of remorse.” Horn would often give a warning first to those he suspected of rustling and was said to have been a “tremendous presence” whenever he was in the vicinity. Tom’s hatred of rustlers was said to have come from him being a victim to their stealing. Fergie Mitchell, a rancher of the North Laramie River described Horn’s reputation: “So one day Tom Horn visited the North Laramie. I saw him ride by. He didn’t stop, but went straight on up the creek in plain sight of everyone. All he wanted was to be seen, as his reputation was so great that his presence in a community had the desired effect. Within a week three settlers in the neighborhood sold their holdings and moved out. That was the end of cattle rustling on the North Laramie.”

Later, hiring out as a gunman, Horn took part in the Pleasant Valley War in Arizona between cattlemen and sheepmen. Historians have not established which side he worked for, and both sides suffered several killings for which no known suspects were ever identified. Horn worked in Arizona for a time as a deputy sheriff, where he drew the attention of the Pinkerton Detective agency due to his tracking abilities. Hired by the agency circa late 1889 or early 1890, he handled investigations in Colorado and Wyoming, in other western states, and around the Rocky Mountain area, working out of the Denver office. He became known for his calm under pressure, and his ability to track down anyone assigned to him.

In one case, Horn and another agent, C. W. Shores, captured two men who had robbed the Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad (on August 31, 1890) between Cotopaxi and Texas Creek in Fremont County, Colorado. Horn and Shores tracked and arrested Thomas Eskridge (aka “Peg-Leg” Watson) and Burt “Red” Curtis without firing a shot. They tracked them all the way to the home of a man named Wolfe, said to be in either Washita or Pauls Valley, Oklahoma, along the Washita River. In his report on that arrest, Horn stated in part “Watson, was considered by everyone in Colorado as a very desperate character. I had no trouble with him.”

During the Johnson County War, he worked for the Wyoming Stock Grower’s Association. He is alleged to have been involved in the killing of Nate Champion and Nick Ray on April 9, 1892. The Pinkerton Agency forced Horn to resign in 1894. In his memoir, Two Evil Isms: Pinkertonism and Anarchism, Pinkerton detective Charlie Siringo wrote that “William A. Pinkerton told me that Tom Horn was guilty of the crime, but that his people could not allow him to go to prison while in their employ.” Siringo would later indicate that he respected Horn’s abilities at tracking, and that he was a very talented agent, but had a wicked element. In 1895, Horn reportedly killed a known cattle thief named William Lewis near Iron Mountain, Wyoming. Horn was exonerated for that crime and for the 1895 murder of Fred Powell six weeks later. In 1896, a ranchman named Campbell, known to have a large stash of cash, was last seen with Horn.

Although his official title was “Range Detective,” Horn essentially served as a killer for hire. By the mid-1890s the cattle business in Wyoming and Colorado was changing due to the arrival of homesteaders and new ranchers. The homesteaders, “nesters” or “grangers”, as they were referred to by the big operators, had moved into the territory in large numbers. By doing so they decreased the availability of water for the herds of the larger cattle barons.

In 1900, Horn had begun working for the Swan Land and Cattle Company in northwest Colorado. His first job was to investigate the Browns Park Cattle Association’s leader and cowboy Matt Rash, who was suspected of cattle-rustling. Horn went undercover as “Tom Hicks” and worked for Rash as a ranch hand, while also collecting evidence of Rash branding cattle that did not belong to him. When Horn finally pieced together enough evidence to determine that Rash was indeed a rustler, he put a letter on Rash’s door threatening him to leave in sixty days, but Rash defiantly stayed. As Rash continued to be uncooperative, Horn’s employers were said to have given the assassin the “go-ahead signal” to execute Rash. On the day of the murder, an armed Horn arrived at Rash’s cabin as the man had just finished eating. Horn then shot him point-blank. The dying Rash unsuccessfully tried to write the name of his killer, but no trace was left of the murder. Only the accounts and rumors from various people point to Horn as the one responsible. Rash was supposed to be married to a nearby rancher, Ann Bassett, and the woman accused Hicks of being the murderer.

At that time Horn also suspected another cowboy named Isom Dart of rustling. Dart was one of Rash’s fellow cowboys, but was believed to have been a rustler named Ned Huddleston, a former member of the late “Tip Gault” gang. The gang, which had rustled cattle in the Saratoga area, was wiped out in a gun battle. Dart also had three indictments returned against him in Sweetwater County. When Dart was accused of murdering Rash, he took refuge inside his friend’s cabin and waited for the rumors to cool down. Horn however, managed to track down Dart to his cabin, and saw him hiding together with two other armed associates. The assassin was said to have set up a sniping position under the cover of a pine tree, overlooking the cabin from a hill. As Dart and his friends came out of the cabin, Horn shot him in the chest from a distance. Prior to the assassination, Horn instructed a rancher named Robert Hudler to ready a horse miles from the murder scene for his getaway. The next day, two .30-30 shells were found at the base of a tree where it was believed that the murderer had laid in wait. Hicks was said to have been the only one in the area to use a 30-30. Afterwards, Horn killed three other members of the Rash’s association, and the story goes that he pinned one of the dead cowboy’s ears at the homesteaders as a warning.

During the Wilcox Train Robbery investigation, Horn obtained information from Bill Speck that revealed which of the robbers had killed Sheriff Josiah Hazen, killed during pursuit of the robbers. Either George Curry or Kid Curry were said to have killed the sheriff. Both outlaws were members of Butch Cassidy’s Wild Bunch gang, then known as “The Hole-in-the-Wall Gang,” for their hideaway in the mountains. Horn passed this information on to Charlie Siringo, who was working the case for the Pinkertons. Horn briefly entered the United States Army to serve during the Spanish American War. Before leaving Tampa for Cuba with the troops, Horn contracted yellow fever and was judged unfit for combat. After recovering, he returned to Wyoming. Shortly after his return, in 1901 Horn began working for wealthy cattle baron John C. Coble, who belonged to the Wyoming Stock Men’s Association.

While working again near Iron Mountain, Wyoming, Horn visited the Jim and Dora Miller family on July 15, 1901. They were cattle ranchers. (Jim Miller was no relation to the Texas outlaw Jim Miller.) Jim Miller and his neighbor Kels Nickell had already had several disputes following Nickell’s introduction of sheep into the Iron Mountain area. Miller frequently accused Nickell of letting his sheep graze on Miller land. At the Millers, Horn met Glendolene M. Kimmell, the young teacher at the Iron Mountain School. Ms. Kimmell was supported by both the large Miller and Kels Nickell families, and she boarded with the Millers. Horn entertained her with accounts of his adventures. That day he and males of the Miller family went fishing; he and Victor Miller, a son about his age, also practiced shooting, both of them with .30-.30s.

The Miller and Nickell families were the only ones to have children at the school. Kimmel had been advised of the families’ feud before she arrived, and found that it was often played out by conflict among the children. A few days later, on July 18, 1901, Willie Nickell, the 14-year-old son of sheep ranchers Kels and Mary Nickell, was found murdered near their homestead gate. A coroner’s inquest began to investigate the murder. More violent incidents occurred during the period of the coroner’s inquest, which was expanded to investigate these incidents, and lasted from July through September 1901.

On August 4, 1901, Kels Nickell was shot and wounded. Some 60-80 of his sheep were found “shot or clubbed to death.” Two of the younger Nickell children later reported seeing two men leaving on horses colored a bay and a gray, as were horses owned by Jim Miller. (Bay is a common color among horses). On August 6, l901 Deputy Sheriff Peter Warlaumont and Deputy U.S. Marshal Joe LeFors came to Iron Mountain and arrested Jim Miller and his sons Victor and Gus on suspicion of shooting Kels Nickell. They were jailed on August 7 and released the following day on bond. The investigation of the shooting of Kels Nickell was added to the investigation of Willie Nickell’s murder in the coroner’s inquest.

Deputy Marshal Joe Lefors later questioned Horn in January 1902 about the murder, while supposedly talking to him about employment. Horn was still inebriated from the night before, but Lefors gained what he called a confession to the murder of Willie Nickell. Horn allegedly confessed to killing the young Willie with his rifle from 300 yards, which he boasted as the “best shot that [he] ever made and the dirtiest trick that [he] ever done.” Horn was arrested the next day by the county sheriff. Walter Stoll was the Laramie County Prosecutor in the case. Judge Richard H. Scott, who presided over the case, was running for reelection.

Horn was supported by his longtime friend and employer, cattle rancher John C. Coble. He gathered a team for the defense headed by Judge John W. Lacey, and included attorneys T.F. Burke, Roderick N. Matson, Edward T. Clark and T. Blake Kennedy. Reportedly, Coble paid for most of the costs of this large team. According to Johan P. Bakker, who wrote Tracking Tom Horn, the large cattle interests by this time found Horn “expendable” and the case provided a way to silence him in regard to their activities. He wrote that 100 members of the Wyoming Stock Growers Association paid $1000 each toward the defense, but wanted a minimal effort.

Horn’s trial started October 10, 1902 in Cheyenne, which filled with crowds attracted by the notoriety of Horn. The Rocky Mountain News noted the carnival atmosphere and great interest from the public for a conviction. The prosecution introduced Horn’s confession to Lefors. Only certain parts of Horn’s statement were introduced, distorting his statement. The prosecution introduced testimony by at least two witnesses, including lawman Lefors, as well as circumstantial evidence; these elements only placed Horn in the general vicinity of the crime scene. During the trial, Victor Miller testified that he and Horn both had .30-.30 guns, and bought their ammunition at the same store. Another, Otto Plaga, testified that Horn was 20 miles from the scene of the murder an hour after it was committed. Glendolene Kimmell had testified during the coroner’s inquest, saying she thought both the Miller and Nickell families responsible for maintaining the feud, but she was never called as a defense witness. She had resigned from the school in October 1901 and left the area, but was in communication with people in the case. She submitted an affidavit to the governor while the case was on appeal. It is recounted in secondary sources but the original document disappeared from public records.

Horn’s trial went to the jury on October 23, and they returned a guilty verdict the next day.[ A hearing several days later sentenced Horn to death by hanging. Horn’s attorneys filed a petition with the Wyoming Supreme Court for a new trial. While in jail, Horn wrote his autobiography, Life of Tom Horn, Government Scout and Interpreter, Written by Himself, mostly giving an account of his early life. It contained little about the case. The Wyoming Supreme Court upheld the decision of the District Court and denied a new trial. Convinced of Horn’s innocence, Glendolene Kimmell sent an affidavit to Governor Fenimore Chatterton with testimony reportedly saying that Victor Miller was guilty of Nickell’s murder. Accounts of its contents appeared in the press, but the original document has disappeared. The governor chose not to intervene in the case. Horn was given an execution date of November 20, 1903.

Tom Horn was one of the few people in the “Wild West” to have been hanged by a water-powered gallows, known as the “Julian Gallows.” James P. Julian, a Cheyenne, Wyoming architect, designed the contraption in 1892. The trap door was connected to a lever which pulled the plug out of a barrel of water. This would cause a lever with a counterweight to rise, pulling on the support beam under the gallows. When enough pressure was applied, the beam broke free, opening the trap and hanging the condemned man. Horn was hanged in Cheyenne. At that time, Horn never gave up the names of who those who had hired him during the feud. He was buried in the Columbia Cemetery in Boulder, Colorado on 3 December 1903. Rancher Jim Coble paid for his coffin and a stone to mark his grave.

Born

- November, 21, 1860

- USA

- Scotland County, Missouri

Died

- November, 20, 1903

- USA

- Cheyenne, Wyoming

Cause of Death

- Execution by hanging

Cemetery

- Columbia Cemetery

- Boulder, Colorado

- USA