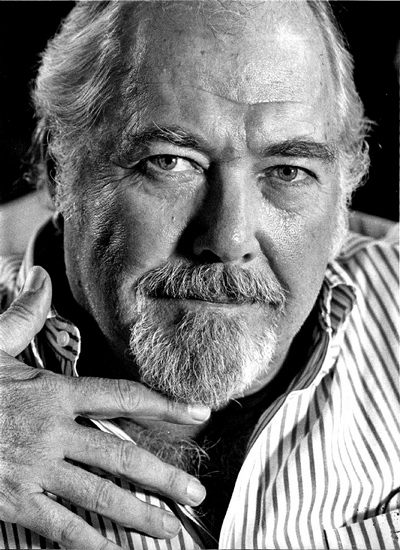

Robert Altman (Robert Altman)

Altman was born in Kansas City, Missouri, the son of Helen (née Matthews), a Mayflower descendant from Nebraska, and Bernard Clement Altman, a wealthy insurance salesman and amateur gambler, who came from an upper-class family. Altman’s ancestry was German, English and Irish; his paternal grandfather, Frank Altman, Sr., anglicized the spelling of the family name from “Altmann” to “Altman”. Altman had a Catholic upbringing, but he did not continue to practice as a Catholic as an adult, although he has been referred to as “a sort of Catholic” and a Catholic director. He was educated at Jesuit schools, including Rockhurst High School, in Kansas City. He graduated from Wentworth Military Academy in Lexington, Missouri in 1943. In 1943 Altman joined the United States Army Air Forces at the age of 18. During World War II, Altman flew more than 50 bombing missions as a crewman on a B-24 Liberator with the 307th Bomb Group in Borneo and the Dutch East Indies.

Upon his discharge in 1946, Altman moved to California. He worked in publicity for a company that had invented a tattooing machine to identify dogs. He entered filmmaking on a whim, selling a script to RKO for the 1948 picture Bodyguard, which he co-wrote with George W. George. Altman’s immediate success encouraged him to move to New York City, where he attempted to forge a career as a writer. Having enjoyed little success, in 1949 he returned to Kansas City, where he accepted a job as a director and writer of industrial films for the Calvin Company. In February 2012, an early Calvin film directed by Altman, Modern Football (1951), was found by filmmaker Gary Huggins.

Altman directed some 65 industrial films and documentaries before being hired by a local businessman in 1956 to write and direct a feature film in Kansas City on juvenile delinquency. The film, titled The Delinquents, made for $60,000, was purchased by United Artists for $150,000, and released in 1957. While primitive, this teen exploitation film contained the foundations of Altman’s later work in its use of casual, naturalistic dialogue. With its success, Altman moved from Kansas City to California for the last time. He co-directed The James Dean Story (1957), a documentary rushed into theaters to capitalize on the actor’s recent death and marketed to his emerging cult following.

Altman’s first forays into TV directing were on the DuMont drama series Pulse of the City (1953–1954), and an episode of the 1956 western series The Sheriff of Cochise. After Alfred Hitchcock saw Altman’s early features The Delinquents and The James Dean Story, he hired him as a director for his CBS anthology series Alfred Hitchcock Presents. After just two episodes, Altman resigned due to differences with a producer, but this exposure enabled him to forge a successful TV career. Over the next decade Altman worked prolifically in television (and almost exclusively in series dramas) directing multiple episodes of Whirlybirds, The Millionaire, U.S. Marshal, The Troubleshooters, The Roaring 20s, Bonanza, Bus Stop, Kraft Mystery Theater, Combat!, and Kraft Suspense Theatre, as well as single episodes of several other notable series including Hawaiian Eye, Maverick, Lawman, Surfside 6, Peter Gunn, and Route 66.

Through this early work on industrial films and TV series, Altman experimented with narrative technique and developed his characteristic use of overlapping dialogue. He also learned to work quickly and efficiently on a limited budget. During his TV period, though frequently fired for refusing to conform to network mandates, as well as insisting on expressing political subtexts and antiwar sentiments during the Vietnam years, Altman always was able to gain assignments. In 1964, the producers decided to expand “Once Upon a Savage Night”, one of his episodes of Kraft Suspense Theatre, for theatrical release under the name, Nightmare in Chicago. Two years later, Altman was hired to direct the low-budget space travel feature Countdown, but was fired within days of the project’s conclusion because he had refused to edit the film to a manageable length. He did not direct another film until That Cold Day in the Park (1969), which was a critical and box-office disaster.

In 1969 Altman was offered the script for MASH, an adaptation of a little-known Korean War-era novel satirizing life in the armed services; more than a dozen other filmmakers had passed on it. Altman had been hesitant to take the production, and the shoot was so tumultuous that Elliott Gould and Donald Sutherland tried to have Altman fired over his unorthodox filming methods. Nevertheless, MASH was widely hailed as an immediate classic upon its 1970 release. It won the Palme d’Or at the 1970 Cannes Film Festival and netted six Academy Award nominations. It was Altman’s highest-grossing film, released during a time of increasing anti-war sentiment in the United States.

Now recognized as a major talent, Altman notched critical successes with McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971), a Western known for its gritty portrayal of the American frontier; The Long Goodbye (1973), a controversial adaptation of the Raymond Chandler novel (scripted by Leigh Brackett) now ranked as a seminal influence on the neo-noir subgenre; Thieves Like Us (1974), an adaptation of the Edward Anderson novel previously filmed by Nicholas Ray as They Live by Night (1949); and Nashville (1975), which had a strong political theme set against the world of country music. The stars of the film wrote their own songs; Keith Carradine won an Academy Award for the song “I’m Easy”. None of these films grossed in excess of $10 million, but most were profitable; Nashville grossed over $9.9 million on a $2.2 million budget, a strategy that Altman would depend upon for funding for much of his career. Although his films were often met with divisive notices, many of the prominent film critics of the era (including Pauline Kael, Vincent Canby and Roger Ebert) remained steadfastly loyal to his oeuvre throughout the decade.

Audiences took some time to appreciate his films, and he did not want to have to satisfy studio officials. In 1970, following the release of MASH, he founded Lion’s Gate Films to have independent production freedom. Altman’s company is not to be confused with the current Lionsgate, a Canada/U.S. entertainment company. The films he made through his company included Brewster McCloud, A Wedding, 3 Women, and Quintet.

In 1980, he directed the musical Popeye. Produced by Robert Evans and written by Jules Feiffer, the film was based on the comic strip/cartoon of the same name and starred the comedian Robin Williams in his film debut. Designed as a vehicle to increase Altman’s commercial clout following a series of critically acclaimed but commercially unsuccessful low-budget films in the late 1970s (including 3 Women, A Wedding and Quintet), the production (filmed on location in Malta) was beleaguered by heavy drug and alcohol use among most of the cast and crew, including the director; Altman reportedly clashed with Evans, Williams (who threatened to leave the film) and songwriter Harry Nilsson (who departed midway through the shoot, leaving Van Dyke Parks to finish the orchestrations). Though critically unsuccessful, the film grossed $60 million worldwide on a $20 million budget and was the second highest-grossing film Altman had directed to that point.

In 1981, the director sold Lion’s Gate to producer Jonathan Taplin after his political satire Health shot in 1979 was still shelved in 1980 by longtime distributor 20th Century Fox following tepid test screenings in the wake of the departure of his avowed partisan Alan Ladd, Jr. from the studio. Unable to secure major financing in the post-New Hollywood blockbuster era because of his long-established mercurial reputation and the particularly tumultuous events surrounding the production of Popeye, Altman began to “direct literate dramatic properties on shoestring budgets for stage, home video, television, and limited theatrical release,” including the acclaimed Secret Honor and Come Back to the Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean, an adaptation of a play that Altman had directed on Broadway.[12] An abortive return to Hollywood filmmaking, the buddy film O.C. and Stiggs was shelved by MGM for nearly two years and received a belated limited commercial release in 1987. He also garnered a good deal of acclaim for his TV “mockumentary” Tanner ’88, based on a presidential campaign, for which he earned an Emmy Award and regained critical favor. Still, widespread popularity with audiences continued to elude him.

He revitalized his career with The Player (1992), a satire of Hollywood. Co-produced by the influential David Brown (The Sting, Jaws, Cocoon), the film was nominated for three Academy Awards, including Best Director. While he did not win the Oscar, he was awarded Best Director by the Cannes Film Festival, BAFTA, and the New York Film Critics Circle.

Altman then directed Short Cuts (1993), an ambitious adaptation of several short stories by Raymond Carver, which portrayed the lives of various citizens of Los Angeles over the course of several days. The film’s large cast and intertwining of many different storylines were similar to his large-cast films of the 1970s; he won the Golden Lion at the 1993 Venice International Film Festival and another Oscar nomination for Best Director. In 1996, Altman directed Kansas City, expressing his love of 1930s jazz through a complicated kidnapping story. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1999. Altman directed Gosford Park (2001), and his portrayal of a large-cast, British country house mystery was included on many critics’ lists of the ten best films of that year. It won the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay (Julian Fellowes) plus six more nominations, including two for Altman, as Best Director and Best Picture.

Working with independent studios such as the now-shuttered Fine Line, Artisan (which was absorbed into today’s Lionsgate), and USA Films (now Focus Features), gave Altman the edge in making the kinds of films he has always wanted to make without studio interference. A film version of Garrison Keillor’s public radio series A Prairie Home Companion was released in June 2006. Altman was still developing new projects up until his death, including a film based on Hands on a Hard Body: The Documentary (1997).

In 2006, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences awarded Altman an Academy Honorary Award for Lifetime Achievement. During his acceptance speech, he revealed that he had received a heart transplant approximately ten or eleven years earlier. The director then quipped that perhaps the Academy had acted prematurely in recognizing the body of his work, as he felt like he might have four more decades of life ahead of him.

Born

- February, 20, 1925

- USA

- Kansas City, Missouri

Died

- November, 20, 2006

- USA

- West Hollywood, California

Other

- Cremated, Ashes scattered at sea.