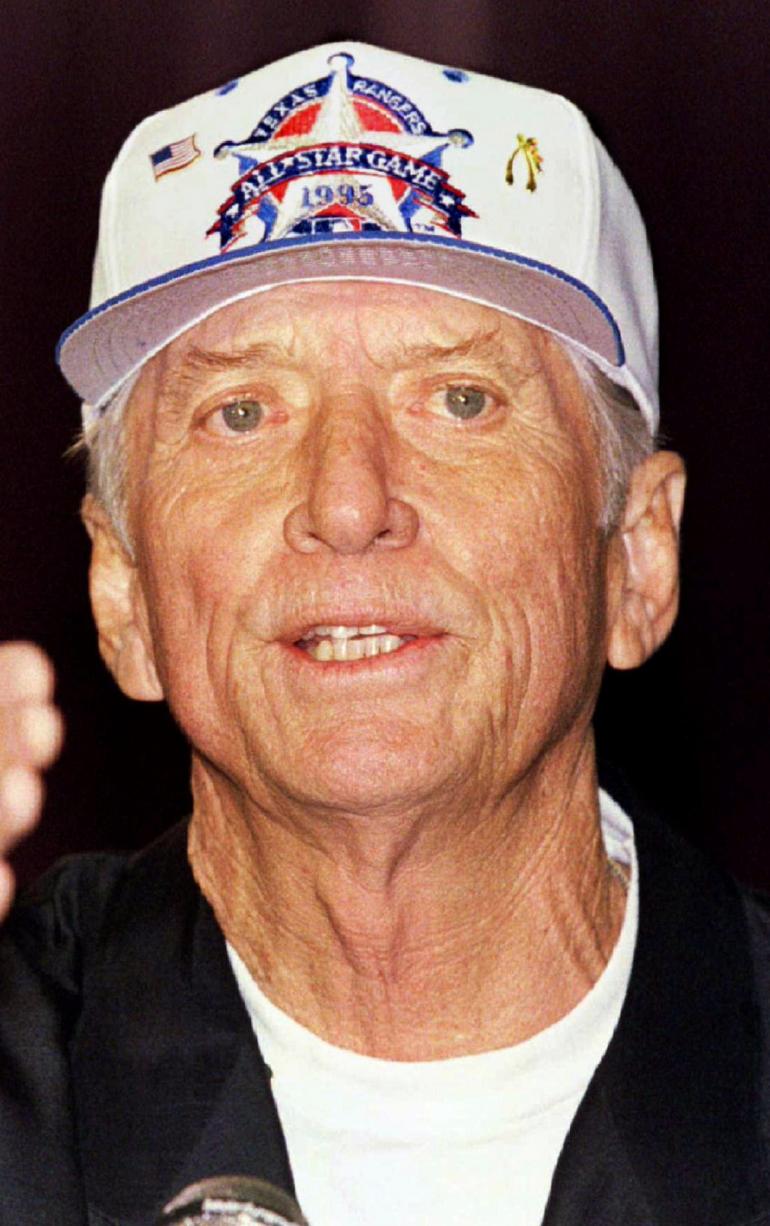

Mickey Mantle (Mickey Mantle)

Mickey Mantle was born in Spavinaw, Oklahoma, the son of Elvin Charles Mantle (1912-1952), a lead miner known as “Mutt,” and Lovell (née Richardson) Mantle (1904-1995). He was of at least partial English ancestry; his great-grandfather, George Mantle, left Brierley Hill, in England’s Black Country, in 1848.

Mutt named his son in honor of Mickey Cochrane, a Hall of Fame catcher. Later in his life, Mantle expressed relief that his father had not known Cochrane’s true first name, as he would have hated to be named Gordon. Mantle spoke warmly of his father, and said he was the bravest man he ever knew. “No boy ever loved his father more,” he said. Mantle batted left-handed against his father when he practiced pitching to him right-handed and he batted right-handed against his grandfather, Charles Mantle, when he practiced throwing to him left-handed. His grandfather died at the age of 60 in 1944, and his father died of Hodgkin’s disease at the age of 40 on May 7, 1952.

When Mickey was four years old, his family moved to the nearby town of Commerce, Oklahoma, where his father worked in lead and zinc mines. As a teenager, Mantle rooted for theSt. Louis Cardinals. Mantle was an all-around athlete at Commerce High School, playing basketball as well as football (he was offered a football scholarship by the University of Oklahoma) in addition to his first love, baseball. His football playing nearly ended his athletic career, and indeed his life. Kicked in the left shin during a practice game during his sophomore year, Mantle’s left ankle soon became infected with osteomyelitis, a crippling disease that was incurable just a few years earlier. A midnight drive to Tulsa, Oklahoma enabled him to be treated with newly available penicillin, saving his swollen left leg from amputation.

Mantle began his professional career with the semi-professional Baxter Springs Whiz Kids. In 1948, Yankees’ scout Tom Greenwade came to Baxter Springs to watch Mantle’s teammate, third baseman Billy Johnson. During the game, Mantle hit three home runs. Greenwade returned in 1949, after Mantle’s high school graduation, to sign Mantle to a minor league contract. Mantle signed for $140 per month ($1,388 today) with a $1,500 ($14,868 today) signing bonus.

Mantle was assigned to the Yankees’ Class-D Independence Yankees of the Kansas–Oklahoma–Missouri League, where he played shortstop. During a slump, Mantle called his father to tell him he wanted to quit baseball. Mutt drove to Independence and convinced Mantle to keep playing baseball. Mantle hit .313 for the Independence Yankees. In 1950, Mantle was promoted to the Class-C Joplin Miners of the Western Association. Mantle won the Western Association batting title, with a .383 average. He also hit 26 home runs and recorded 136 runs batted in. However, Mantle struggled defensively at shortstop.

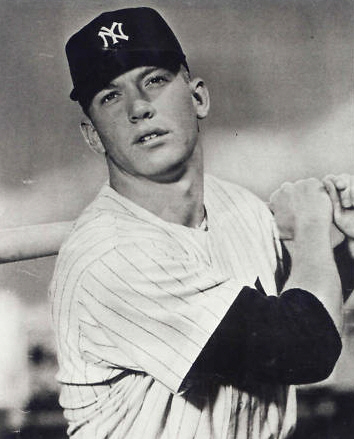

Mantle was invited to the Yankees instructional camp before the 1951 season. After an impressive spring training, Yankees manager Casey Stengel decided to promote Mantle to the majors as a right fielder instead of sending him to the minors. Mickey Mantle’s salary for the 1951 season was $7,500.

Mantle was assigned uniform #6, signifying the expectation that he would become the next Yankees star, following Babe Ruth (#3), Lou Gehrig (#4) and Joe DiMaggio (#5). Stengel, speaking to SPORT, stated “He’s got more natural power from both sides than anybody I ever saw.” Bill Dickey called Mantle “the greatest prospect [he’s] seen in [his] time.”

After a brief slump, Mantle was sent down to the Yankees’ top farm team, the Kansas City Blues. However, he was not able to find the power he once had in the lower minors. Out of frustration, he called his father one day and told him, “I don’t think I can play baseball anymore.” Mutt drove up to Kansas City that day. When he arrived, he started packing his son’s clothes and, according to Mantle’s memory, said “I thought I raised a man. I see I raised a coward instead. You can come back to Oklahoma and work the mines with me.” Mantle immediately broke out of his slump, going on to hit .361 with 11 homers and 50 RBIs during his stay in Kansas City.

Mantle was called up to the Yankees after 40 games with Kansas City, this time wearing uniform #7. He hit .267 with 13 home runs and 65 RBI in 96 games. In the second game of the 1951 World Series, New York Giants rookie Willie Mays hit a fly ball to right-center field. Mantle, playing right field, raced for the ball together with center fielder Joe DiMaggio, who called for the ball (and made the catch). In getting out of DiMaggio’s way, Mantle tripped over an exposed drain pipe and severely injured his right knee. This was the first of numerous injuries that plagued his 18-year career with the Yankees. He played the rest of his career with a torn ACL. After his injury he was timed from the left side of the batters box, with a full swing, to run to first base in 3.1 seconds. That has never been matched, even without a swing.

Mantle moved to center field in 1952, replacing DiMaggio, who retired at the end of the 1951 season. He was named to the American League All-Star roster for the first time but did not play (5-inning game). Mantle played center field full-time until 1965, when he was moved to left field. His final two seasons were spent at first base. Among his many accomplishments are all-time World Series records for home runs (18), runs scored (42), and runs batted in (40).

Although the osteomyelitic condition of Mantle’s left leg had exempted him from being drafted for military service since he had turned 18 in 1949, emergence as a star in the major leagues during the Korean Conflict led to questioning of his 4-F deferment by baseball fans. Two Armed Forces physicals were ordered as a Yankee, including a highly publicized exam brought on by his 1952 selection as an All-Star. Conducted on November 4, 1952, it ended in a final rejection.

After showing progressive improvement each of his first five years, Mantle had a breakout season in 1956. Described by him as his “favorite summer,” his major league leading .353 batting average, 52 home runs, and 130 runs batted in brought home both the Triple Crown and first of three MVP awards. His performance was so exceptional he was bestowed the Hickok Belt as the top American professional athlete of the year. Mantle is the only player to win a league Triple Crown as a switch hitter.

Mantle won his second consecutive MVP in 1957 behind league leads in runs and walks, a career-high .365 batting average (second to Ted Williams’ .388), and hitting into a league-low five double plays. Mantle reached base more times than he made outs (319 to 312), one of two seasons in which he achieved the feat.

On January 16, 1961, Mantle became the highest-paid player in baseball by signing a $75,000 ($591,899 today) contract. DiMaggio, Hank Greenberg, and Ted Williams, who had just retired, had been paid over $100,000 in a season, and Ruth had a peak salary of $80,000. Mantle became the highest-paid active player of his time. Mickey Mantle’s top salary was $100,000 which he reached for the 1963 season. Having reached that pinnacle in his 13th season, he never asked for another raise.

During the 1961 season, Mantle and teammate Roger Maris, known as the M&M Boys, chased Babe Ruth’s 1927 single-season home run record. Five years earlier, in 1956, Mantle had challenged Ruth’s record for most of the season, and the New York press had been protective of Ruth on that occasion also. When Mantle finally fell short, finishing with 52, there seemed to be a collective sigh of relief from the New York traditionalists. Nor had the New York press been all that kind to Mantle in his early years with the team: he struck out frequently, was injury-prone, was a “true hick” from Oklahoma, and was perceived as being distinctly inferior to his predecessor in center field, Joe DiMaggio.

Over the course of time, however, Mantle (with a little help from his teammate Whitey Ford, a native of New York’s Borough of Queens) had gotten better at “schmoozing” with the New York media, and had gained the favor of the press. This was a talent that Maris, a blunt-spoken upper-Midwesterner, was never willing or able to cultivate; as a result, he wore the “surly” jacket for his duration with the Yankees. So as 1961 progressed, the Yanks were now “Mickey Mantle’s team,” and Maris was ostracized as the “outsider,” and said to be “not a true Yankee.” The press seemed to root for Mantle and to belittle Maris. Mantle was unexpectedly hospitalized by an abscessed hip he got from a flu shot late in the season, leaving Maris to break the record (he finished with 61). Mantle finished with 54 home runs while leading the American league in runs scored and walks.

In 1962 and 1963, he batted .321 and .314. In 1964, Mantle hit .303 with 35 home runs and 111 RBIs. In the bottom of the ninth inning of Game 3 of the 1964 World Series against the St. Louis Cardinals, Mantle blasted Barney Schultz’s first pitch into the right field stands at Yankee Stadium, which won the game for the Yankees 2–1. The homer, his 16th World Series round tripper, broke the World Series record of 15 set by Babe Ruth. He hit two more homers in the series to set the existing World Series record of 18 home runs. The Cardinals ultimately won the World Series in 7 games.

The Yankees and Mantle were slowed down by injuries during the 1965 season, and they finished in 6th place, 25 games behind the Minnesota Twins. He hit .255 with 19 home runs and 46 RBIs. In 1966, his batting average increased to .288 with 23 home runs and 56 RBIs. After the 1966 season, he was moved to first base with Joe Pepitone taking over his place in the outfield. On May 14, 1967 (Mother’s Day) Mantle became the fifth member of the 500 Homerun Club. During his final season (1968), Mantle hit .237 with 18 home runs and 54 RBIs.

Mantle was selected as an American League All-Star in 1968 for the 16th and final time, his pinch hit at-bat on July 11 making his appearance in 19 of the 20 games he had been named to (MLB having had two All-Star games a year from 1959 to 1962). During his eighteen year career he was selected every season but 1951 and 1966, and failed to appear when chosen only in 1952.

Mantle announced his retirement on March 1, 1969. When he retired, Mantle was third on the all-time home run list with 536. At the time of his retirement, Mantle was the Yankees all-time leader in games played with 2,401, which was broken by Derek Jeter on August 29, 2011.

Mantle hit some of the longest home runs in Major League history. On September 10, 1960, he hit a ball left-handed that cleared the right-field roof at Tiger Stadium in Detroit and, based on where it was found, was estimated years later by historian Mark Gallagher to have traveled 643 feet (196 m). Another Mantle homer, hit right-handed off Chuck Stobbs at Griffith Stadium in Washington, D.C. on April 17, 1953, was measured by Yankees traveling secretary Red Patterson (hence the term “tape-measure home run”) to have traveled 565 feet (172 m). Deducting for bounces, there is no doubt that both landed well over 500 feet (152 m) from home plate. Mantle twice hit balls off the third-deck facade at Yankee Stadium, nearly becoming the only player to hit a fair ball out of the stadium during a game. On May 22, 1963, against Kansas City’s Bill Fischer, Mantle hit a ball that fellow players and fans claimed was still rising when it hit the 110-foot (34 m) high facade, then caromed back onto the playing field. It was later estimated by some that the ball could have traveled 504 feet (154 m) had it not been blocked by the ornate and distinctive facade. On August 12, 1964, he hit one whose distance was undoubted: a center field drive that cleared the 22-foot (6.7 m) batter’s eye screen, some 75′ beyond the 461-foot (141 m) marker at the Stadium.

Although he was a feared power hitter from either side of the plate and hit more home runs batting left-handed than right, Mantle considered himself a better right-handed hitter. In roughly 25% of his total at-bats he hit .330 right-handed to .281 left. His 372 to 164 home run disparity was due to Mantle having batted left-handed much more often, as the large majority of pitchers are right-handed. In spite of short foul pole dimension of 296 feet (90 m) to left and 302 feet (92 m) to right in original Yankee Stadium, Mantle gained no advantage there as his stroke both left and right-handed drove balls there to power alleys of 344′ to 407′ and 402′ to 457′ feet (139 m) from the plate. Overall, he hit slightly more home runs away (270) than home (266).

Mickey Mantle’s career was plagued with injuries. Beginning in high school, he suffered both acute and chronic injuries to bones and cartilage in his legs. Applying thick wraps to both of his knees became a pre-game ritual, and by the end of his career simply swinging a bat caused him to fall to one knee in pain. Baseball scholars often ponder “what if” had he not been injured, and had been able to lead a healthy career.

As a 19-year-old rookie in his first World Series, Mantle tore the cartilage in his right knee on a fly ball by Willie Mays while playing right field. Joe DiMaggio, in the last year of his career, was playing center field. Mays’ fly was hit to shallow center, and as Mantle came over to back up DiMaggio, Mantle’s cleats caught a drainage cover in the outfield grass. His knee twisted awkwardly and he instantly fell. Witnesses say it looked “like he had been shot.” He was carried off the field on a stretcher and watched the rest of the World Series on TV from a hospital bed. Dr. Stephen Haas, medical director for the National Football League Players Association, has speculated that Mantle may have torn his anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) during the incident and played the rest of his career without having it properly treated since ACLs could not be repaired with the surgical techniques available in that era. Still, Mantle was known as the “fastest man to first base” and won the American League triple crown in 1956. In 1949, he received a draft-examine notice and was about to be drafted by the US Army but failed the physical exam and was rejected as unqualified and was given a 4-F deferment for any military service.

During the 1957 World Series, Milwaukee Braves second baseman Red Schoendienst fell on Mantle’s left shoulder in a collision at second base. Over the next decade, Mantle experienced increasing difficulty hitting from his left side.

Mantle made a (talking) cameo appearance in Teresa Brewer’s 1956 song “I Love Mickey,” which extolled Mantle’s power hitting. The song was included in one of the Baseball’s Greatest Hits CDs.

In 1962, Mantle and Maris starred as themselves in Safe at Home!. In 1981, he had a cameo appearance in the White Shadow and Remington Steele with Whitey Ford in 1983.

Mantle served as a part-time color commentator on NBC’s baseball coverage in 1969, teaming with Curt Gowdy and Tony Kubek to call some Game of the Week telecasts as well as that year’s All-Star Game. In 1972 he was a part-time TV commentator for the Montreal Expos.

Despite being among the best-paid players of the pre-free agency era, Mantle was a poor businessman, making several bad investments. His lifestyle was restored to one of luxury, and his hold on his fans raised to an amazing level, by his position of leadership in the sports memorabilia craze that swept the USA, beginning in the 1980s. Mantle was a prized guest at any baseball card show, commanding fees far in excess of any other player for his appearances and autographs. This popularity continues long after his death, as Mantle-related items far outsell those of any other player except possibly Babe Ruth, whose items, due to the distance of years, now exist in far smaller quantities. Mantle insisted that the promoters of baseball card shows always include one of the lesser-known Yankees of his era, such as Moose Skowron or Hank Bauer so that they could earn some money from the event.

Despite the failure of Mickey Mantle’s Country Cookin’ restaurants in the early 1970s, Mickey Mantle’s Restaurant & Sports Bar opened in New York at 42 Central Park South (59th Street) in 1988. It became one of New York’s most popular restaurants, and his original Yankee Stadium Monument Park plaque is displayed at the front entrance. Mantle let others run the business operations, but made frequent appearances.

In 1983, Mantle worked at the Claridge Resort and Casino in Atlantic City, New Jersey, as a greeter and community representative. Most of his activities were representing the Claridge in golf tournaments and other charity events. But Mantle was suspended from baseball by Commissioner Bowie Kuhn on the grounds that any affiliation with gambling was grounds for being placed on the “permanently ineligible” list. Kuhn warned Mantle before he accepted the position that he would have to place him on the list if Mantle went to work there. Hall of Famer Willie Mays, who had also taken a similar position, had already had action taken against him. Mantle accepted the position, regardless, as he felt the rule was “stupid.” He was placed on the list, but reinstated on March 18, 1985, by Kuhn’s successor, Peter Ueberroth. In 1992, Mantle wrote My Favorite Summer 1956 about his 1956 season.

On December 23, 1951, Mantle married Merlyn Johnson (1932-2009) in Commerce, Oklahoma; they had four sons. In an autobiography, Mantle said he married Merlyn not out of love, but because he was told to by his domineering father. While his drinking became public knowledge during his lifetime, the press (per established practice at the time) kept quiet about his many marital infidelities. Mantle was not entirely discreet about them, and when he went to his retirement ceremony in 1969, he brought his mistress along with his wife. In 1980, Mickey and Merlyn separated for 15 years, but neither filed for divorce. During this time, Mantle lived with his agent, Greer Johnson.

The couple’s four sons were Mickey Jr. (1953–2000), David (born 1955), Billy (1957–94), whom Mickey named for Billy Martin, his best friend among his Yankee teammates, and Danny (born 1960). Like Mickey, Merlyn and their sons all became alcoholics, and Billy developed Hodgkin’s disease, as had several previous men in Mantle’s family.

During the final years of his life, Mantle purchased a luxury condominium on Lake Oconee near Greensboro, Georgia, near Greer Johnson’s home, and frequently stayed there for months at a time. He occasionally attended the local Methodist church, and sometimes ate Sunday dinner with members of the congregation. He was well liked by the citizens of Greensboro, and seemed to like them in return. This was probably because the town respected Mantle’s privacy, refusing either to talk about their famous neighbor to outsiders or to direct fans to his home. In one interview, Mickey stated that the people of Greensboro had “gone out of their way to make me feel welcome, and I’ve found something there I haven’t enjoyed since I was a kid.”

Mantle’s off-field behavior is the subject of the book The Last Boy: Mickey Mantle and the End of America’s Childhood, written in 2010 by sports journalist Jane Leavy. Excerpts from the book have been published in Sports Illustrated. Mantle is the uncle of actor and musician Kelly Mantle.

Well before he finally sought treatment for alcoholism, Mantle admitted his hard living had hurt both his playing and his family. His rationale was that the men in his family had all died young, so he expected to die young as well. His father died of Hodgkin’s disease at age 40 in 1952, and his grandfather also died young of the same disease. “I’m not gonna be cheated,” he would say. Mantle did not know at the time that most of the men in his family had inhaled lead and zinc dust in the mines, which contribute to Hodgkins’ and other cancers. As the years passed, and he outlived all the men in his family by several years, he frequently used a line popularized by football legend Bobby Layne, a Dallas neighbor and friend of Mantle’s who also died in part due to alcohol abuse: “If I’d known I was gonna live this long, I’d have taken a lot better care of myself.”

Mantle’s wife and sons all completed treatment for alcoholism, and told him he needed to do the same. He checked into the Betty Ford Clinic on January 7, 1994, after being told by a doctor that his liver was so badly damaged from almost 40 years of drinking that it “looked like a doorstop.” He also bluntly told Mantle that the damage to his system was so severe that “your next drink could be your last.” Also helping Mantle to make the decision to go to the Betty Ford Clinic was sportscaster Pat Summerall, who had played for the New York Giants football team while they played at Yankee Stadium, by then a recovering alcoholic and a member of the same Dallas-area country club as Mantle; Summerall himself had been treated at the clinic in 1992.

Shortly after Mantle completed treatment, his son Billy died on March 12, 1994, at age 36 of heart problems brought on by years of substance abuse. Despite the fears of those who knew him that this tragedy would send him back to drinking, he remained sober. Mickey Jr. later died of liver cancer on December 20, 2000, at age 47. Danny later battled prostate cancer.

Mantle spoke with great remorse of his drinking in a 1994 Sports Illustrated cover story. He said that he was telling the same old stories, and realizing how many of them involved himself and others being drunk – including at least one drunk-driving accident – he decided they were not funny anymore. He admitted he had often been cruel and hurtful to family, friends, and fans because of his alcoholism, and sought to make amends. He became a born-again Christian because of his former teammate Bobby Richardson, an ordained Baptist minister who shared his faith with him. After the bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City on April 19, 1995, Mantle joined with fellow Oklahoman and Yankee Bobby Murcer to raise money for the victims.

Mantle received a liver transplant at Baylor University Medical Center in Dallas, on June 8, 1995. His liver was severely damaged by alcohol-induced cirrhosis, as well as hepatitis C. Prior to the operation, doctors also discovered he had inoperable liver cancer known as an undifferentiated hepatocellular carcinoma, further facilitating the need for a transplant. In July, he had recovered enough to deliver a press conference at Baylor, and noted that many fans had looked to him as a role model. “This is a role model: Don’t be like me,” a frail Mantle said. He also established the Mickey Mantle Foundation to raise awareness for organ donations. Soon, he was back in the hospital, where it was found that his cancer was rapidly spreading throughout his body.

Though Mantle was very popular, his liver transplant was a source of some controversy. Some felt that his fame had permitted him to receive a donor liver in just one day, bypassing other patients who had been waiting for much longer. Mantle’s doctors insisted that the decision was based solely on medical criteria, but acknowledged that the very short wait created the appearance of favoritism. While he was recovering, Mantle made peace with his estranged wife, Merlyn, and repeated a request he made decades before for Bobby Richardson to read a poem at Mantle’s funeral if he died.

Mantle died on August 13, 1995, at Baylor University Medical Center with his wife at his side, five months after his mother had died at age 91. The Yankees played Cleveland that day and honored him with a tribute. Eddie Layton played “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” on the Hammond organ because Mickey had once told him it was his favorite song. The team played the rest of the season with black mourning bands topped by a small number 7 on their left sleeves. Mantle was interred in the Sparkman-Hillcrest Memorial Park Cemetery in Dallas. In eulogizing Mantle, sportscaster Bob Costas described him as “a fragile hero to whom we had an emotional attachment so strong and lasting that it defied logic.” Costas added: “In the last year of his life, Mickey Mantle, always so hard on himself, finally came to accept and appreciate the distinction between a role model and a hero. The first, he often was not. The second, he always will be. And, in the end, people got it.” Richardson did oblige in reading the poem at Mantle’s funeral, something he described as being extremely difficult.

After Mantle’s death, Greer Johnson was taken to federal court in November 1997 by the Mantle family to stop her from auctioning many of Mantle’s personal items, including a lock of hair, a neck brace, and expired credit cards. Eventually, the two sides reached a settlement, ensuring the sale of some of Mickey Mantle’s belongings for approximately $500,000.

Born

- October, 20, 1931

- USA

- Spavinaw, Oklahoma

Died

- August, 13, 1995

- USA

- Dallas, Texas

Cemetery

- Sparkman Hillcrest Memorial Park

- Dallas, Texas

- USA