Mel Allen (Mel Allen)

Allen was born in Birmingham, Alabama. (Biographer Stephen Borelli noted that he added the second middle name Avrom after his deceased grandfather.) He attended the University of Alabama, where he was a member of the Kappa Nu Fraternity as an undergraduate.

During his time at Alabama, Israel served as the public address announcer for Alabama Crimson Tide football games. In 1933, when the station manager or sports director of Birmingham’s radio station WBRC asked Alabama coach Frank Thomas to recommend a new play-by-play announcer, he suggested Allen. His first broadcast was Alabama’s home opener that year, against the Tulane Green Wave.

Allen graduated from the University of Alabama School of Law in 1937. Shortly after graduating, Allen took a train to New York City for a week’s vacation. While on that week’s vacation, he auditioned for a staff announcer’s position at the CBS Radio Network. CBS executives already knew of Allen; the network’s top sportscaster, Ted Husing, had heard many of his Crimson Tide broadcasts. He was hired at $45 a week. He often did non-sports announcing such as for big band remotes, or “emceeing” game shows such as Truth or Consequences, serving as an understudy for both sportscaster Husing and newscaster Bob Trout.

In his first year at CBS, he announced the crash of the Hindenburg when the station cut away from singer Kate Smith’s show. He first became a national celebrity when he ad libbed for a half-hour during the rain-delayedVanderbilt Cup from an airplane. In 1939, he was the announcer for the Warner Brothers & Vitaphone film musical short-subject, On the Air, with Leith Stevens and the Saturday Night Swing Club.

Stephen Borelli, in his biography How About That?! (a favorite expression of Allen’s after an outstanding play by the home team), states that it was at CBS’s suggestion in 1937, the year Melvin Israel joined the network, that he go by a different last name on the air. He chose Allen, his father’s middle name as well as his own, and legally changed his name to Melvin Allen in 1943.

Allen became the color commentator for the 1938 World Series. This led Wheaties to tap him to replace Arch McDonald as the voice of the Washington Senators for the 1939 season, who was moving on to New York as the first full-time radio voice of both the Yankees and the New York Giants for their home games. Senators’ owner Clark Griffith wanted Walter Johnson, a former Senators pitcher, instead of Allen, and Wheaties relented.

In June 1939, Garnett Marks, McDonald’s partner on Yankee broadcasts, twice mispronounced Ivory Soap, the Yankees’ sponsor at the time, as “Ovary Soap.” He was fired, and Allen was tapped to replace him. McDonald himself went back to Washington after only one season, and Allen became the Yankees’ and Giants’ lead announcer, doing double duty for both teams because only their home games were broadcast at that time.

He periodically recounted an anecdote that occurred during his first full season (1940) as Yankee play-by-play man. Hall of Fame first baseman Lou Gehrig had been forced to retire the year before after having been diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a fatal illness. Speaking with Allen in the Yankee dugout, Gehrig told him “Mel, I never got a chance to listen to your games before because I was playing every day. But I want you to know they’re the only thing that keeps me going.” Allen broke down in tears after Gehrig departed.

Allen’s stint with the Yankees and Giants was interrupted in 1941, when no sponsor could be found and both teams went off the air, but the broadcasts resumed in 1942. Allen was the voice of both the Yankees and the Giants until 1943, when he entered the United States Army during World War II, broadcasting on The Army Hour and Armed Forces Radio.

After the war, Allen called Yankee games exclusively. By this time, road games were added to the broadcast schedule. Before long Allen and the Yankees were fused in the public consciousness, particularly because of the Yankees’ frequent World Series appearances. He eventually called 22 World Series on radio and television, including 18 in a row from 1946 to 1963. Even when the Yankees did not win the American League pennant and play in the Series, he was so popular with his nationwide audience that he was always tapped as one of the play-by-play men. He also called 24 All-Star Games.

Allen was one of the first three celebrities spoofed in the just-created Mad satirical comic book. In the second issue, Allen, Giant manager Leo Durocher and Hall of Fame Yankee catcher Yogi Berra were all caricatured in a baseball story, “Hex!”, illustrated by Jack Davis. His likeness was also licensed by Standard Comics for a two-issue “Mel Allen’s Sports Comics” series between 1949 and 1950.

After Russ Hodges departed from the Yankee booth to become the longtime voice of the New York (and starting in 1958, San Francisco) Giants, the young Curt Gowdy replaced him as Allen’s broadcast partner in 1949 & 1950, having been brought in from Oklahoma City after winning a national audition. Gowdy, originally from Wyoming, credited Mel Allen’s mentoring as a big factor in his own success as a broadcaster, and became the voice of the Boston Red Sox from 1951 to 1965. Red Barber became Allen’s broadcast partner in 1954, and stayed on with the Yankees after the latter’s dismissal following the 1964 season.

Among Allen’s many catchphrases were “Hello there, everybody!” to start a game, “How a-bout that?!” on outstanding Yankee plays, “Go-ing, go-ing, gonnne!!” for Yankee home runs, for full counts, “Three and two. What’ll he do?” and after a robust Yankee swing and miss, “He took a good cut!”

Allen lost his voice late in the fourth and last game of the 1963 World Series, in which the Dodgers swept the Yankees in four games and their longtime announcer, Vin Scully, paired with Allen on the national telecast, spontaneously took over from him for the end of the game after he could no longer talk, telling him soothingly, “That’s all right, Mel.” (Scully had announced the first half of the game, and Allen had begun to announce the second half.)

Allen called a number of college football bowl games, including 14 Rose Bowls, two Orange Bowls, and two Sugar Bowls. In the National Football League, Allen served as play-by-play announcer for the Washington Redskins in 1952 and 1953 and for the New York Giants on WCBS-AM in 1960, with some of the Giants’ broadcasts also carried nationally by the CBS Radio Network. He also did radio play-by-play for the Miami Dolphins’ inaugural season in 1966, and for Miami Hurricanes football the following year.

Allen hosted Jackpot Bowling on NBC in 1959 after Leo Durocher had left to return to major league baseball coaching, but his lack of bowling knowledge made him an unpopular host and Bud Palmer replaced him as the show’s host in April. In the early 1960s, Allen hosted the three-hour Saturday morning segment of the weekend NBC Radio program Monitor. He also contributed sportscasts to the program until the late 1960s. Allen also provided voiceover narration for Fox Movietone newsreels for many years.

In September 1964, before the end of the season, the Yankees informed Allen that his contract with the team would not be renewed. In those days, the main announcers for both Series participants always called the World Series on NBC television. Although Allen was thus technically eligible to call the 1964 World Series, Baseball Commissioner Ford Frick honored the Yankees’ request to have retired Yankee star shortstop Phil Rizzuto, Allen’s sidekick in the radio booth, join the Series crew instead. It was the first time Allen had missed a Yankee World Series since 1943, and only the second World Series (not counting 1943-44-45, when he was in the military during World War II) that he’d missed since he began calling Yankee games in 1938.

On December 17, 1964, after much media speculation and many letters to the Yankees from fans disgruntled by Allen’s absence from the Series, the Yankees issued a terse press release announcing Allen’s firing; he was replaced by Joe Garagiola. NBC and Movietone dropped him soon afterward. To this day, the Yankees have never given an explanation for the sudden firing, and rumors abounded. Depending on the rumor, Allen was either homosexual, an alcoholic, a drug addict, or had a nervous breakdown. Allen’s sexuality was sometimes a target in those much more socially conservative days because he had not married (and never did marry).

Years later, Allen told author Curt Smith that the Yankees had fired him under pressure from the team’s longtime sponsor, Ballantine Beer. According to Allen, he was fired as a cost-cutting move by Ballantine, which had been experiencing poor sales for years (it would eventually be sold in 1969). Smith, in his book Voices of Summer, also indicated that the medications Allen took to see him through his busy schedule may have affected his on-air performance. (Stephen Borelli, another biographer, has also pointed out that Allen’s heavy workload did not allow him time to take care of his health.)

Allen became Merle Harmon’s partner for Milwaukee Braves games in 1965, and worked Cleveland Indians games on television in 1968. But he would not commit to either team full-time, nor to the Oakland Athletics, who also wanted to hire him after the team’s move from Kansas City. Despite the firing in 1964, Allen remained loyal to the Yankees for the remainder of his life, and to this day—years after his death -— he is still popularly known as “the Voice of the Yankees.”

The Yankees eventually brought Allen back to emcee special Yankee Stadium ceremonies, including Old Timers’ Day, which Allen had originally handled when he was lead announcer. Although Yankee broadcaster Frank Messer, who joined the club in 1968, replaced him as emcee for Old Timers’ Day and other special events like Mickey Mantle Day, the Yankees continued to invite Allen to call the actual exhibition game between the Old Timers, and to take part in players’ number-retirement ceremonies.

Allen was brought back to the Yankees’ on-air team in 1976 as a pre/post-game host for the cable telecasts with John Sterling, and also started calling play-by-play again. He announced Yankees cable telecasts on SportsChannel New York (now MSG Plus) with Phil Rizzuto, Bill White, Frank Messer, and occasionally, Fran Healy.

Allen remained with the Yankees’ play-by-play crew until 1985 and made occasional appearances on Yankee telecasts and commercials into the late 1980s. In 1990, Allen called play-by-play for a WPIX Yankees game to officially make him baseball’s first seven-decade announcer. Among the memorable moments Allen called in his latter stretch were Yankee outfielder Reggie Jackson’s 400th home run in 1980, and Yankee pitcher Dave Righetti’s no-hitter on July 4, 1983.

In his later years, Allen was exposed to a new audience as the host of the syndicated highlights show This Week in Baseball, which he hosted from its inception in 1977 until his death. When FOX relaunched TWIB in 2000 (after a one-year hiatus), it used a claymation version of Allen to open and close the show until 2002.

Allen recorded the play-by-play for two computer baseball games, Tony La Russa Baseball and Old Time Baseball, which were published by Stormfront Studios. The games included his signature “How about that?!” home run call. He also used the same catch-phrase during his cameo appearances in the films The Naked Gun (1988) and Needful Things (1993).

The National Sportscasters and Sportswriters Association inducted Allen into its Hall of Fame in 1972. In 1978, he was one of the first two winners of the Baseball Hall of Fame’s Ford C. Frick Award for broadcasting, along with Red Barber. In 1985, Allen was inducted into the American Sportscasters Association Hall of Fame along with former Yankee partner (and later Red Sox and NBC Sports voice) Curt Gowdy and Chicago legend Jack Brickhouse. He was inducted into the National Radio Hall of Fame in 1988. In 2009, the American Sportscasters Association ranked Allen as the #2 greatest sportscaster of all time, second only to Vin Scully.

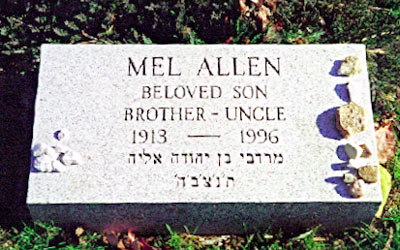

Allen died on June 16, 1996, of heart failure (he had undergone open-heart surgery in 1989) at the age of 83. His one-week vacation in New York City had turned into 60 years.

He was buried at Temple Beth El Cemetery in Stamford, Connecticut. On July 25, 1998, the Yankees dedicated a plaque in his memory for Monument Park at Yankee Stadium. The plaque calls him “A Yankee institution, a national treasure” and includes his much-spoken line “How about that?!”

Born

- February, 14, 1913

- USA

- Birmingham, Alabama

Died

- June, 16, 1996

- USA

- Greenwich, Connecticut

Cemetery

- Beth-el Cemetery

- Stamford, Connecticut

- USA