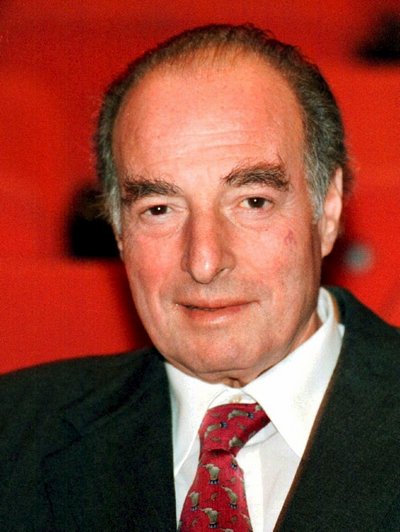

Marc Rich (Marc Rich)

Rich was born in 1934 to a Jewish family in Antwerp, Belgium. His parents were working-class Jews who emigrated with their son to the United States in 1941 to escape the Nazis. His father opened a jewelry store in Kansas City, Missouri. The family moved to Queens, New York City in 1950, where Rich’s father started a company that imported Bengali jute to make burlap bags. Rich’s father later started a business trading agricultural products and helped found the American Bolivian Bank. Rich attended high school at the Rhodes Preparatory School in Manhattan. He later attended New York University, but dropped out after one semester to go work for Philipp Brothers (now known as Phibro LLC) in 1954. He worked as a commodities trader for his father, who sought to build an American manufacturing fortune through burlap-sack production. Rich married Denise Eisenberg, a songwriter and heir to a New England shoe manufacturing fortune, in 1966. They had three children, one of whom, Gabrielle Rich Aouad, died at age 27 of leukemia in 1996. The couple divorced in 1996; she continued to use the name Denise Rich. Six months later he married Gisela Rossi, although that marriage also ended in divorce, in 2005.

He worked with Philipp Brothers, a dealer in metals, learning about the international raw materials markets and commercial trading with poor, third-world nations. He helped run the company’s operations in Cuba, Bolivia, and Spain. In 1974 he and co-worker Pincus Green set up their own company in Switzerland, Marc Rich & Co. AG, which would later become Glencore Xstrata Plc. Nicknamed “the King of Oil” by his business partners, Rich has been said to have expanded the spot market for crude oil in the early 1970s, drawing business away from the larger established oil companies that had relied on traditional long-term contracts for future purchases. As Andrew Hill of the Financial Times put it, “Rich’s key insight was that oil – and other raw materials – could be traded with less capital, and fewer assets, than the big oil producers thought, if backed by bank finance. It was this highly leveraged business model that became the template for modern traders, including Trafigura, Vitol, and Glencore….”

His tutelage under Philipp Brothers afforded Rich the opportunity to develop relationships with various dictatorial régimes and embargoed nations. Rich would later tell biographer Daniel Ammann that he had made his “most important and most profitable” business deals by violating international trade embargoes and doing business with the apartheid regime of South Africa. He also counted Fidel Castro’s Cuba, Marxist Angola, the Nicaraguan Sandinistas, Muammar Gaddafi’s Libya, Nicolae Ceausescu’s Romania, and Augusto Pinochet’s Chile among the clients he serviced. According to Ammann, “he had no regrets whatsoever…. He used to say ‘I deliver a service. People want to sell oil to me and other people wanted to buy oil from me. I am a businessman, not a politician.”

One of his biggest market coups came during the 1973-1974 Arab oil embargo, when he used his Middle Eastern contacts to circumvent the embargo and buy crude oil from Iran and Iraq. After purchasing the crude for roughly US$12 per barrel, Rich doubled the price and sold it to supply-starved U.S. oil companies. Later, following the overthrow of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the Shah of Iran, during the Iranian Revolution in 1979, Rich used his special relationship with Ayatollah Khomeini, the leader of the revolution, to buy oil from Iran despite the American embargo. Iran would become Rich’s most important supplier of crude oil for more than 15 years. Due to his good relationship with Iran, Rich helped give Mossad’s agents contacts in Iran.

His company, Marc Rich Real Estate GmbH, is involved in large developer projects (e.g., in Prague, Czech Republic). Rich was accused of being involved with the Bank of Credit and Commerce International. Rich and Marvin Davis bought 20th Century Fox in 1981. With Rich a fugitive, Davis sold Rich’s interest to Rupert Murdoch for $250 million in March 1984.

In 1983 Rich and partner Pincus Green were indicted on 65 criminal counts, including income tax evasion, wire fraud, racketeering, and trading with Iran during the oil embargo (at a time when Iranian revolutionaries were still holding American citizens hostage). The charges would have led to a sentence of more than 300 years in prison had Rich been convicted on all counts. The indictment was filed by then-U.S. Federal Prosecutor (and future mayor of New York City) Rudolph Giuliani. At the time it was the biggest tax evasion case in U.S. history.

Hearing of the plans for the indictment, Rich fled to Switzerland and, always insisting that he was not guilty, never returned to the U.S. to answer the charges. Rich’s companies eventually pled guilty to 35 counts of tax evasion and paid $90 million in fines, although Rich himself remained on the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Ten Most-Wanted Fugitives List for many years, narrowly evading capture in Britain, Germany, Finland, and Jamaica. Fearing arrest, he did not even return to the United States to attend his daughter’s funeral in 1996.

On January 20, 2001, hours before leaving office, U.S. President Bill Clinton granted Rich what would prove to be a highly controversial presidential pardon. Several of Clinton’s strongest supporters distanced themselves from the decision. Former President Jimmy Carter, a fellow Democrat, said, “I don’t think there is any doubt that some of the factors in his pardon were attributable to his large gifts. In my opinion, that was disgraceful.” Clinton himself would later express regret for issuing the pardon, saying that “it wasn’t worth the damage to my reputation.” Clinton’s critics alleged that Rich’s pardon had been bought, as Denise Rich had given more than $1 million to Clinton’s political party (the Democratic Party), including more than $100,000 to the Senate campaign of the president’s wife, Hillary Rodham Clinton, and $450,000 to the Clinton Library foundation during Clinton’s time in office. Clinton explained his decision by noting that similar cases were settled in civil, not criminal court.

Clinton also cited clemency pleas he had received from Israeli government officials, including then-Prime Minister Ehud Barak. Rich had made substantial donations to Israeli charitable foundations over the years, and many senior Israeli officials, such as Shimon Peres and Ehud Olmert, argued on his behalf behind the scenes. (Speculation about another rationale for Rich’s pardon involved his alleged involvement with the Israeli intelligence community.[28][29] Rich reluctantly acknowledged in interviews with his biographer, Daniel Ammann, that he had assisted the Mossad, Israel’s intelligence service, a claim that Ammann said was confirmed by a former Israeli intelligence officer. According to Ammann, Rich had helped finance the Mossad’s operations and had supplied Israel with strategic amounts of Iranian oil through a secret oil pipeline. The aide to Rich who had persuaded Denise Rich to personally ask President Clinton to review Rich’s pardon request was a former chief of the Mossad, Avner Azulay. Another former Mossad chief, Shabtai Shavit, had also urged Clinton to pardon Rich, whom he said had routinely allowed intelligence agents to use his offices around the world.)

Federal Prosecutor Mary Jo White was appointed to investigate Clinton’s last-minute pardon of Rich. She stepped down before the investigation was finished and was replaced by James Comey, who was critical of Clinton’s pardons and of then-Deputy Attorney General Eric Holder’s pardon recommendation. Rich’s lawyer, Jack Quinn, had previously been Clinton’s White House Counsel and chief of staff to Clinton’s Vice President, Al Gore, and had had a close relationship with Holder. According to Quinn, Holder had advised that standard procedures be bypassed and the pardon petition be submitted directly to the White House. Congressional investigations were also launched. Clinton’s top advisors, Chief of Staff John Podesta, White House Counsel Beth Nolan, and advisor Bruce Lindsey, testified that nearly all of the White House staff advising the president on the pardon request had urged Clinton to not grant Rich a pardon. Federal investigators ultimately found no evidence of criminal activity.

As a condition of the pardon, it was made clear that Rich would drop all procedural defenses against any civil actions brought against him by the United States upon his return there. That condition was consistent with the position that his alleged wrongdoing warranted only civil penalties, not criminal punishment. Rich never returned to the United States.

In a February 18, 2001 op-ed essay in The New York Times, Clinton (by then out of office) explained why he had pardoned Rich, noting that U.S. tax professors Bernard Wolfman of the Harvard Law School and Martin Ginsburg of Georgetown University Law Center had concluded that no crime had been committed, and that Rich’s companies’ tax-reporting position had been reasonable. In the same essay, Clinton listed Lewis “Scooter” Libby as one of three “distinguished Republican lawyers” who supported a pardon for Rich. (Libby himself later received a presidential commutation for his involvement in the Plame affair.) During Congressional hearings after Rich’s pardon, Libby, who had represented Rich from 1985 until the spring of 2000, denied that Rich had violated the tax laws but criticized him for trading with Iran at a time when that country was holding U.S. hostages.

Rich died of a stroke on June 26, 2013, at a Lucerne hospital. He was 78 and is survived by two daughters, Ilona Schachter-Rich and Danielle Kilstock Rich. He was buried in Israel.

Born

- December, 18, 1934

- Antwerp, Belgium

Died

- June, 26, 2013

- Lucerne, Switzerland

Cemetery

- Israel