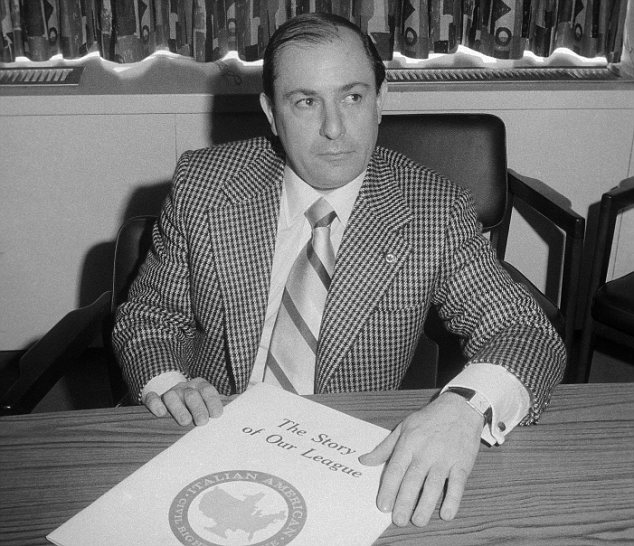

Joseph Colombo (Joseph Anthony Colombo)

Joseph Colombo

Joseph Colombo Sr., the reputed Mafia leader who was a founder of the Italian‐American Civil Rights League —and who was gunned down and left almost totally paralyzed at a 1971 league rally in Columbus Circle — died Monday night at St. Luke’s Hospital in Newburgh, N.Y. He would have been 55 years old on June 16.

Joseph Colombo had been taken in a coma to the hospital on May 6 from his nearby five‐acre estate in Blooming Grove.

Dr. John C. Bivono Jr., a member of the hospital’s staff who had been attending Mr. Colombo, said that while the immediate cause of death was cardiac arrest, Mr. Colombo’s condition stemmed from the seven‐year‐old gunshot wounds.

In a 1975 court‐ordered evaluation of his condition, Joseph Colombo was described as being able to move only the forefinger and thumb of his right hand. A year later, he was reported able to utter a few words and recognize people.

But for the most part, the once‐robust Mr. Colombo, 48 years old when he was cut down, hgd been incapacitated at his estate. The property had formerly been his vacation home, but after the shooting it became a full‐time residence surrounded by bodyguards.

But if Joseph Colombo was no longer active, the Mafia “family” he had allegedly headed still was, according to law enforcement officials and underworld informants. In 1976, they said the Colombo family, under new leadership, was still involved in underworld killings.

And the 1972 slaying of Joseph Gallo in a restaurant in the Little Italy section of Manhattan was also said by some sources to be an outgrowth of the wars between the Colombo and Gallo families —although no one was ever indicted in the Gallo slaying.

Continue reading the main story

Mr. Colombo was shot three times, once in the head, by a young black man named Jerome A. Johnson, who was himself immediately slain at the Columbus Circle rally—a rally that had been given heavy police security. Mr. Johnson’s killer was never caught.

Nonetheless, some law enforcement officials have attributed the shooting of Mr. Colombo to enmity between the group he allegedly headed and Mr. Gallo’s followers.

Although the authorities believed Joseph Anthony Colombo Sr. to be a power in New York City organized crime—the head of a Mafia family with about 200 members and associates—Mr. Colombo was a sharp departure from the men traditionally identified as Mafia leaders.

Most Mafia chieftains shun the limelight with as much determination as they try to avoid the authorities. Mr. Colombo, on the other hand, increasingly thrust himself into the public spotlight, in the years before he was shot, as a selfappointed leader in behalf of ItalianAmerican civil rights.

Mr. Colombo was in Columbus Circle with thousands of his supporters, making last‐minute preparations for a rally sponsored by the Italian‐American Civil Rights League, the group he had played a leading role in founding barely a year before.

The league had come a long way in its short life, claiming a membership of 45,000 and chapters across the country. It had achieved several important victories in behalf of a “positive image” for Italian‐Americans.

But to law enforcement officials, Mr. Colombo was far more than a spokesman for “civil rights,” far more than a real‐estate salesman who lived with his family in a well‐kept split‐level house on 83d Street in the Bay Ridge section of Brooklyn.

To the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and other agencies, Mr. Colombo was a key figure in the world of organized crime.

At the time he was shot, Mr. Colombo was under indictment on charges of controlling a $10‐million‐a‐year gambling syndicate in Brooklyn, Manhattan and Nassau County, and was under a second indictment on charges of income‐tax evasion.

He was implicated in a jewel robbery in Nassau County, was facing a contempt charge in Brooklyn and was free on bail pending an appeal of a conviction for having committed perjury in his application for a real‐estate broker’s license.

The conviction was for lying about a criminal record that included 13 arrests and three convictions—two fines for gambling and a 30‐day contempt sentence.

Mr. Colombo was not the first in his family to meet with violence. His father, Anthony, was killed in 1938 in a gangland war, when Joseph was a teen‐ager.

Joseph Colombo was born in Brooklyn on June 16, 1923. After two years at New Utrecht High School and three years in the Coast Guard, from which he was discharged in 1945 because he suffered from “psychoneurosis,” he is believed to have drifted into a life of petty crime.

Most of his arrests were on such charges as running a craps game, consorting with known gamblers or criminals, dfsorderly conduct and vagrancy. For 10 years he worked intermittently as a longshoreman and for six he was employed as a salesman for a meat company controlled by the brother of a Mafia leader. In the years before he was shot, Mr. Colombo had been a salesman with the Cantalupo Realty Company in Bensonhurst.

According to law enforcement officials, Mr. Colombo reached a position of power in 1964, when he was given leadership of a family headed by Guiseppe Magliocco.

When Joseph Bonanno, leader of a New York family and a member of the Mafia national commission, allegedly decided to try to become the dominant force in the Mafia, his reported plan called for the murder of three Mafia leaders.

Law officials said that Mr. Colombo, then a newly appointed captain in the Magliocco family, was delegated to carry out the assassinations.

But Mr. Colombo informed Carlo Gambino, one of the intended victims of the plan, the law enforcement officials said, and was apparently rewarded with the, leadership of Mr. Magliocco’s family when that crime figure died shortly after.

The Colombo family’s rackets, according to the authorities, include numbers and sports gambling, hijacking, fencing stolen goods and loan‐sharking. In keeping with the “new look” among younger Mafia leaders, Mr. Colombo was believed to have interests in 20 legitimate businesses in New York.

To this portrayal by the authorities, Mr. Colombo responded with ridicule.

“Mafia; what’s the Mafia?” he asked. “There is not a Mafia. Am I head of a family? Yes, my wife and four sons and a daughter. That’s my family.”

He asserted that the F.B.I. encouraged the spread of the terms “Mafia” and “Cosa Nostra” to conceal its investigative inadequacies, and he declared that these words were a slander on all ItalianAmericans.

It was this theme, and the F.B.I.’s “harassment” of him and his family, that Mr. Colombo stressed as he took his case to the public—in striking contrast to the behavior of other reputed Mafia leaders.

The Italian — American Civil Rights League grew out of demonstrations in the spring of 1970, when Mr, Colombo began leading a nightly picketing of the F.B.I.’s Manhattan offices to protest the prosecution of his son Joseph Jr. on charges of conspiring to melt silver coins into more valuable ingots.

Joseph Jr. was acquitted after the Government’s chief witness recanted his testimony.

The league, with Natale Marcone, a former union organizer, as president and with Mr. Colombo’s son Andrew as vice president, grew in membership and activity.

A concert at the Felt Forum helped raise $500,000, a testimonial dinner in Huntington, L.I., netted $101,000.

The producer of “The Godfather,” a film adaptation of the best‐selling novel, agreed to the league’s demand to delete references to the Mafia from the script, as did the producers of the television series “The F.B.I.” Public officials, including Attorney General John N. Mitchell and Gov. Nelson A. Rockefeller, muted references to the Mafia and Cosa Nostra.

Today the Italian‐American Civil Rights League is far less in the news, but it is still active in such community programs as getting summer jobs for youths and aiding the elderly, according to Carl Cecora, its national president.

He said yesterday that the group had 15 chapters in various parts of the country—including seven in the New York area—and a total membership of 35,000. There were 52 chapters and 200,000 members at the group’s height he said, but that “we’re building.”

Mr. Colombo is survived by his wife, Lucille, and their four sons and a daughter.

Mr. Colombo’s body was taken to the Prospero funeral home in his native Brooklyn. A service was scheduled for 9:30 A.M. Friday at St. Bernadettes Roman Catholic Church, in the borough’s Bensonhurst section.

Born

- June, 16, 1924

- Brooklyn, New York City

Died

- May, 22, 1978

- Blooming Grove, New York

Cause of Death

- Cardiac arrest

Cemetery

- Saint John Cemetery

- Queens, New York