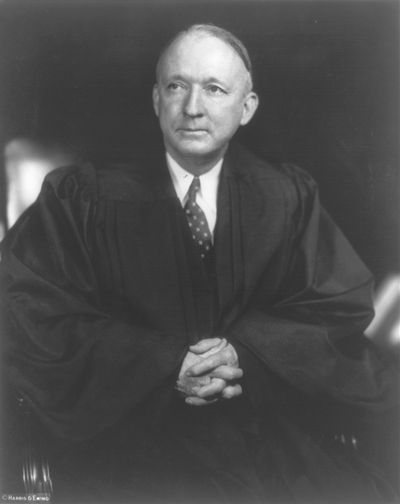

Hugo Lafayette Black (Hugo Lafayette Black)

Hugo LaFayette Black was the youngest of the eight children of William Lafayette Black and Martha Toland Black. He was born on February 27, 1886, in a small wooden farmhouse in Ashland, Alabama, a poor, isolated rural Clay County town in the Appalachian foothills. Because his brother Orlando had become a medical doctor, Hugo decided at first to follow in his footsteps. At age seventeen, he left school and enrolled at Birmingham Medical School. However, it was Orlando who suggested that Hugo should enroll at the University of Alabama School of Law. After graduating in June 1906, he moved back to Ashland and established a legal practice. His legal practice was not a success, so Black moved to Birmingham in 1907 to continue his law practice, and came to specialize in labor law and personal injury cases.

Following his defense of an African American forced into a form of commercial slavery following incarceration, Black was befriended by A. O. Lane, a judge connected with the case. When Lane was elected to the Birmingham City Commission in 1911, he asked Black to serve as a police court judge, an experience that would be his only judicial experience prior to the Supreme Court. In 1912, Black resigned that seat in order to return to practicing law full-time. He was not done with public service; in 1914, he began a four-year term as the Jefferson County Prosecuting Attorney.

Three years later, during World War I, Black resigned in order to join the United States Army, eventually reaching the rank of captain. He served in the 81st Field Artillery, but was not assigned to Europe. He joined the Birmingham Civitan Club during this time, eventually serving as president of the group. He remained an active member throughout his life, occasionally contributing articles to Civitan publications. On February 23, 1921, he married Josephine Foster (1899–1951), with whom he would have three children: Hugo L. Black, II (1922-2013), an attorney; Sterling Foster (1924-1996), and Martha Josephine (born 1933). Josephine died in 1951; in 1957, Black married Elizabeth Seay DeMeritte.

In 1921, Black successfully defended E. R. Stephenson in the sensationalistic trial for the murder of a Catholic priest, Father James E. Coyle. He joined the Ku Klux Klan shortly after, thinking it necessary for his political career. Running for the Senate as the “people’s” candidate, Black believed he needed the votes of Klan members. Near the end of his life, Black would admit that joining the Klan was a mistake, but he went on to say “I would have joined any group if it helped get me votes.” Black, along with fellow politician and friend, Bibb Graves, were known in Alabama Klan circles as the Gold Dust Twins.

Scholars and biographers have recently examined Black’s religious views. Ball finds regarding the Klan that Black “sympathized with the group’s economic, nativist, and anti-Catholic beliefs.” Newman says Black “disliked the Catholic Church as an institution” and gave numerous anti-Catholic speeches in his 1926 election campaign to KKK meetings across Alabama. In 1937 The Harvard Crimson reported on Black’s appointment of a Jewish law Clerk, noting that he “earlier had appointed Miss Annie Butt, a Catholic, as a secretary, and the Supreme Court had designated Leon Smallwood, a Negro and a Catholic as his messenger.”

Black was one the Associate Justices who held in Brown v. Board of Education that segregation in public schools is unconstitutional. The plaintiffs were represented by Thurgood Marshall. A decade later, on October 2, 1967 Marshall became the first African American to be appointed Supreme Court, and served with Black on the Court until Black’s retirement on September 17, 1971.

In United States v. Price eighteen Ku Klux Klan members were charged with murder and conspiracy for the deaths of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, but the charges were dismissed by the trial court. A unanimous Supreme Court, which included Black, reversed the dismissal and ordered the case to proceed to trial. Seven of these men, including fellow Klansmen Samuel Bowers, Cecil Price and Alton Wayne Roberts were found guilty of the crime; eight of them, including Lawrence A. Rainey, were found not guilty; and three of them, including Edgar Ray Killen, had their cases end in a mistrial. In 1926, Black sought election to the United States Senate from Alabama, following the retirement of Senator Oscar Underwood. Since the Democratic Party dominated Alabama politics at the time, he easily defeated his Republican opponent, E. H. Dryer, winning 80.9% of the vote. He was reelected in 1932, winning 86.3% of the vote against Republican J. Theodore Johnson.

Senator Black gained a reputation as a tenacious investigator. In 1934, for example, he chaired the committee that looked into the contracts awarded to air mail carriers under Postmaster General Walter Folger Brown, an inquiry which led to the Air Mail scandal. In order to correct what he termed abuses of “fraud and collusion” resulting from the Air Mail Act of 1930, he introduced the Black-McKellar Bill, later the Air Mail Act of 1934. The following year he participated in a Senate committee’s investigation of lobbying practices. He publicly denounced the “highpowered, deceptive, telegram-fixing, letterframing, Washington-visiting” lobbyists, and advocated legislation requiring them to publicly register their names and salaries.

In 1935, Black became chairman of the Senate Committee on Education and Labor, a position he would hold for the remainder of his Senate career. In 1937 he sponsored the Black-Connery Bill, which sought to establish a national minimum wage and a maximum workweek of thirty hours. Although the bill was initially rejected in the House of Representatives, an amended version of it, which extended Black’s original maximum workweek proposal to forty-four hours, was passed in 1938 (after Black left the Senate), becoming the Fair Labor Standards Act. Black was an ardent supporter of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal. In particular, he was an outspoken advocate of the Judiciary Reorganization Bill of 1937, popularly known as the court-packing bill, FDR’s unsuccessful plan to stack a hostile Supreme Court in his favor by adding more associate justices.

Black would throughout his career as a senator give speeches based on his belief in the ultimate power of the Constitution. He came to see the actions of the anti-New Deal Supreme Court as judicial excess; in his view, the Court was improperly overturning legislation passed by large majorities of Congress. During his Senate career Black consistently opposed the passage of Anti-Lynching legislation. In 1935 Black lead a filibuster of the Wagner-Costigan anti-lynching bill. The Pittsburgh Post Gazette reported that when a motion to end the fillibuster was defeated “[t]he southerners- headed by Tom Connally of Texas and Hugo Black of Alabama – grinned at each other and shook hands.”

Soon after the failure of the court-packing plan, President Roosevelt obtained his first opportunity to appoint a Supreme Court Justice when conservative Willis Van Devanter retired. Roosevelt wanted the replacement to be a “thumping, evangelical New Dealer” who was reasonably young, confirmable by the Senate, and from a region of the country unrepresented on the Court. The three final candidates were Solicitor General Stanley Reed, Sherman Minton, and Hugo Black. Roosevelt said Reed “had no fire,” and Minton did not want the appointment at the time. The position would go to Black, a candidate from the South, who, as a senator, had voted for all 24 of Roosevelt’s major New Deal programs. Roosevelt admired Black’s use of the investigative role of the Senate to shape the American mind on reforms, his strong voting record, and his early support, which dated back to 1933.

On August 12, 1937, Roosevelt nominated Black to fill the vacancy. By tradition, a senator nominated for an executive or judicial office was confirmed immediately and without debate. However, when Black was nominated, the Senate departed from this tradition for the first time since 1853; instead of confirming him immediately, it referred the nomination to the Judiciary Committee. Black was criticized for his presumed bigotry, his cultural roots, and his Klan membership, when that became public.

The Judiciary Committee recommended Black’s confirmation by a vote of 13–4 on August 16 of that year. The next day the full Senate considered Black’s nomination. Rumors relating to Black’s involvement in the Ku Klux Klan surfaced among the senators, and two Democratic senators tried defeating the nomination. However, no conclusive evidence of Black’s involvement was available at the time, so after six hours of debate, the Senate voted 63-16 to confirm Black. Ten Republicans and six Democrats voted against Black. Alabama Governor Bibb Graves appointed his own wife, Dixie B. Graves, to fill Black’s vacated seat.

The next month, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette investigated Black’s past. Ray Sprigle won a Pulitzer Prize for his series of articles revealing Black’s involvement in the Klan. However, the controversy soon subsided; the criticism was highly partisan, and polls showed that the attacks had little effect on public opinion of Black. Black also addressed public concerns in person: “I did join the Klan. I later resigned. I never rejoined…. Before becoming a Senator I dropped the Klan. I have had nothing to do with it since that time. I abandoned it. I completely discontinued any association with the organization. I have never resumed it and never expect to do so.” Black was close friends with Walter Francis White, the black executive secretary of the NAACP who would help assuage critics of the appointment. Chambers v. Florida (1940), an early case where Black ruled in favor of African American criminal defendants who experienced due process violations, helped put concerns to rest.

As soon as Black started on the Court, he advocated judicial restraint and worked to move the Court away from interposing itself in social and economic matters. Black vigorously defended the “plain meaning” of the Constitution, rooted in the ideas of its era, and emphasized the supremacy of the legislature; for Black, the role of the Supreme Court was limited and constitutionally prescribed. During his early years on the Supreme Court, Black helped reverse several earlier court decisions taking a narrow interpretation of federal power. Many New Deal laws that would have been struck down under earlier precedents were thus upheld. In 1939 Black was joined on the Supreme Court by Felix Frankfurter and William O. Douglas. Douglas voted alongside Black in several cases, especially those involving the First Amendment, while Frankfurter soon became one of Black’s ideological foes.

In the mid-1940s, Justice Black became involved in a bitter dispute with Justice Robert H. Jackson as a result of Jewell Ridge Coal Corp. v. Local 6167, United Mine Workers (1945). In this case the Court ruled 5–4 in favor of the UMW; Black voted with the majority, while Jackson dissented. However, the coal company requested the Court rehear the case on the grounds that Justice Black should have recused himself, as the mine workers were represented by Black’s law partner of 20 years earlier. Under the Supreme Court’s rules, each Justice was entitled to determine the propriety of disqualifying himself. Jackson agreed that the petition for rehearing should be denied, but refused to give approval to Black’s participation in the case. Ultimately, when the Court unanimously denied the petition for rehearing, Justice Jackson released a short statement, in which Justice Frankfurter joined. The concurrence indicated that Jackson voted to deny the petition not because he approved of Black’s participation in the case, but on the “limited grounds” that each Justice was entitled to determine for himself the propriety of recusal. At first the case attracted little public comment, however, after Chief Justice Harlan Stone died in 1946, rumors that President Harry S. Truman would appoint Jackson as Stone’s successor led several newspapers to investigate and report the Jewell Ridge controversy. Black and Douglas allegedly leaked to newspapers that they would resign if Jackson were appointed Chief. Truman ultimately chose Fred M. Vinson for the position. Black later clashed with fellow Justice Abe Fortas during the 1960s. In 1968, a Warren clerk called their feud “one of the most basic animosities of the Court.”

Vinson’s tenure as Chief Justice coincided with the Red Scare, a period of intense anti-communism in the United States. In several cases the Supreme Court considered, and upheld, the validity of anticommunist laws passed during this era. For example, in American Communications Association v. Douds (1950), the Court upheld a law that required labor union officials to forswear membership in the Communist Party. Black dissented, claiming that the law violated the First Amendment’s free speech clause. Similarly, in Dennis v. United States, 341 U.S. 494 (1951), the Court upheld the Smith Act, which made it a crime to “advocate, abet, advise, or teach the duty, necessity, desirability, or propriety of overthrowing the Government of the United States.” The law was often used to prosecute individuals for joining the Communist Party. Black again dissented, writing:

“Public opinion being what it now is, few will protest the conviction of these Communist petitioners. There is hope, however, that, in calmer times, when present pressures, passions and fears subside, this or some later Court will restore the First Amendment liberties to the high preferred place where they belong in a free society.” Beginning in the late 1940s, Black wrote decisions relating to the establishment clause, where he insisted on the strict separation of church and state. The most notable of these was Engel v. Vitale (1962), which declared state-sanctioned prayer in public schools unconstitutional. This provoked considerable opposition, especially in conservative circles. Efforts to restore school prayer by constitutional amendment failed.

In 1953 Vinson died and was replaced by Earl Warren. While all members of the Court were New Deal liberals, Black was part of the most liberal wing of the Court, together with Warren, Douglas, William Brennan, and Arthur Goldberg. They said the Court had a role beyond that of Congress. Yet while he often voted with them on the Warren Court, he occasionally took his own line on some key cases, most notably Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), which established that the Constitution protected a right to privacy. In not finding such a right implicit in the Constitution, Black wrote in his dissent that “Many good and able men have eloquently spoken and written… about the duty of this Court to keep the Constitution in tune with the times. … For myself, I must with all deference reject that philosophy.” Black’s most prominent ideological opponent on the Warren Court was John Marshall Harlan II, who replaced Justice Jackson in 1955. They disagreed on several issues, including the applicability of the Bill of Rights to the states, the scope of the due process clause, and the one man, one vote principle.

Justice Black admitted himself to the National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, in August 1971, and subsequently retired from the Court on September 17. He suffered a stroke two days later and died on September 25. Services were held at the National Cathedral, and over 1,000 persons attended. Pursuant to Justice Black’s wishes, the coffin was “simple and cheap” and was displayed at the service to show that the costs of burial are not reflective of the worth of the human whose remains were present.

His remains were interred at the Arlington National Cemetery. He is one of twelve Supreme Court justices buried at Arlington. The others are Harry Andrew Blackmun, William J. Brennan, Arthur Joseph Goldberg, Thurgood Marshall, Potter Stewart, William O. Douglas, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., Chief Justice William Howard Taft, Chief Justice Earl Warren, Chief Justice Warren Burger, and Chief Justice William Rehnquist. Justice Black is buried to the right of the main cemetery entrance, and up a hill, 200 yards behind the Taft monument. Black’s headstone is “identical in size and shape to the tens of thousands of military headstones in Arlington.” It says simply, “Hugo Lafayette Black, Captain, U. S. Army”. President Richard Nixon first considered nominating Hershel Friday to fill the vacant seat, but changed his mind after the American Bar Association found Friday unqualified. Nixon then nominated Lewis Powell, who was confirmed by the Senate.

Born

- February, 27, 1886

- USA

- Ashland, Alabama

Died

- September, 25, 1971

- USA

- Bethsada, Maryland

Cemetery

- Arlington National Cemetery

- Arlington, Virginia

- USA