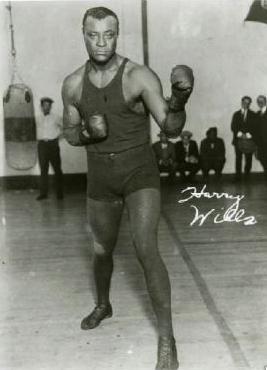

Harry Wills ( )

Harry Wills

Between 1915 and 1927, Harry Wills was one of the best fighters, if not the best, in the heavyweight division. Yet, he never got his chance to fight for the heavyweight championship. Like other black fighters in the early part of the past century, Harry Wills was nothing but a footnote in boxing history. What denied Wills his place in history was the color of his skin. At a time in which the heavyweight championship was considered the purview of the Caucasian race, Harry Wills tilled in the heavyweight division hinterland. After Jack Johnson’s reign as champion ended, white promoters were determined not to allow blacks a whiff at the championship belt.

Jack Johnson’s personal conduct outside the ring scandalized White America, as modesty and humility were not part of his make up. Jack Johnson essentially gave White America the middle finger as he violated every taboo of his time. Jack Johnson found white women more to his liking as he said, “Every colored lady I ever went with two-timed me, white girls didn’t.” And when he was not bedding white women, he was beating white heavyweights. He did not just beat his opponent; he taunted and tortured them before beating them. Sports writer Ring Ladner described Jack Johnson as that “grinning Negro whose delight was in whipping purpose.” Johnson spent the last years of his championship reign outside the country and eventually lost his title to Jess Willard under the scorching Havana sun.

Harry Wills came into his own as a fighter after Johnson relinquished his title in 1915. A strong fighter and big for his era, Harry Wills used his size to an advantage. Black boxing historian Kevin Smith told me in an EMAIL interview that Harry Wills’ skills, “would be considered good for his day. His strength was his asset. He could move other men around the ring as he pleased. He couldn’t understand why he never did receive a title shot. He was considered the top contender for almost seven years. No number one contender could be ignored for that long today — but the racial tones of that time simply would not allow such a bout.”

Kevin Smith added that Wills was at his best during the late teens and the early 20s. If Dempsey had fought Wills then, it would have been a great fight. Luis Firpo, a similar fighter to Wills, nearly ended Dempsey’s reign as champion when he knocked the Manassa Mauler out of the ring. Firpo’s eventual loss did not diminish the fact that a Wills-Dempsey bout in 1920 or 1921 would have been a splendid event. Dempsey was not invincible, as Tunney would later show. Wills developed his boxing skills by fighting several quality opponents, including the great Sam Langford, Sam McVey, and Joe Jeannette.

Harry Wills will be remembered less for the fights that he did fight and more for the championship fight that never came. It is hard to truly judge Wills’ skills, since there are very few films of Wills fighting, and we only have second hand reporting to depend upon. Much of this comes from white reporters, who were biased against the black heavyweight from the Big Easy. Racism denied Wills his shot at heavyweight glory. That is the fact. Kevin Smith stated, “His strength was his asset. He could move other men around the ring as he pleased, then put them in position and land as he saw fit. He was a master of holding and hitting (which in the teens was considered an art form and not frowned upon as much as it is today).” An athletic man for his size with one-punch knock out power, Wills dominated most of the heavyweight division.

Smith considered Wills one of the best between 1915-1922. As he declared, “Besides Dempsey, and an old (but still great) Langford, I can’t see anyone who would be considered a favorite over Wills.” In 1919, Jess Willard decided to put his championship up for grabs. As the Great White Hope who ended the Johnson championship reign, Jess Willard was America’s hero. Having fought only once over the previous four years since defeating Jack Johnson, Willard was ripe for the picking. As with many fighters in the early part of the century, much debate centered about Willard’s boxing skills. Forced into exile due to the Mann Act, Jack Johnson wasn’t the same fighter as the boxer who massacred Jim Jefferies five years earlier. While Willard’s reputation was built on defeating Johnson, Willard beat an old Johnson and merely outlasted the older and less conditioned fighter. It is hard to truly judge Willard, so we only have second-hand accounts gathered through the oral history of past boxing historians as well as newspaper accounts. Nat Fleischer considered Willard, “one of the poorest of the heavyweight champions…. Jess was a slow moving pugilist who disliked training as much as he disliked the sport.” Seymour Rothman of the Toledo Blade provided another point of view when he wrote that Willard “was truly equipped to be a champion. He had a long left arm, which held off eager opponents. His right hand punches were devastating.” Willard’s size and endurance were his major assets.

Tex Rickard, the major boxing promoter from 1910 till his death in 1929, told his financial backers that he would never match Willard with a black fighter. Roger Kahn noted that for Rickard, the issue was as much about money as racism. Rickard told one of his financial backers, “If a nigger wins the championship, then the championship isn’t worth a nickel.” This reasoning eliminated both Sam Langford and Harry Wills. By this time, Langford was past his prime but Wills was at his peak as a fighter. His strength and durability would have made the Willard-Wills fight an interesting proposition. As Kevin Smith told me, “When you meet Sam Langford 18 times over and live to tell about it — you are a serious fighter. I guess it can best be said that Harry Wills was legit. He had size, speed, power, a bit of grace, and a great deal of experience.” Rickard denied Wills his first chance at the heavyweight title. While Kahn would write that Rickard’s major concern was making money, he added that with Rickard, “The issue was money, not prejudice. Or anyway money before prejudice.” Rickard’s racism played a role in denying Wills his shot at the championship throughout his career. (Rickard’s impact can’t be underestimated. Rickard’s control of the sport in the 20s would make modern day promoters Don King and Bob Arum envious.)

After racism eliminated Wills from contention, it created Jack Dempsey’s date with destiny as he destroyed Willard over three rounds in a display of ferocity rarely seen in heavyweight fighting. As Dempsey ruled the heavyweight division, beating what was left of white contenders, Wills toiled unknown to the white boxing audience. With no more legitimate white heavyweights left, Jack Dempsey decided to take a break from fighting in 1923. The only contenders left were a former light heavyweight named Gene Tunney and Harry Wills. Wills, unfortunately, had another opponent — age.

Roger Kahn makes it clear in his autobiography that Jack Dempsey was willing to fight Harry Wills. Dempsey signed contracts to fight Wills on two different occasions but reneged when finances failed to materialize. Roger Kahn noted about Dempsey, “ Not awed by Wills, Dempsey was afraid of something else: boxing without getting paid.” Wills, six years older than Dempsey, was running out of time. Despite being the number one challenger for close to a decade, time was eroding Wills’ skills. The age factor started showing up when he lost to Sharkey and barely beat a raw Luis Firpo. Smith pointed out, “Wills was past his prime when he fought Sharkey and pretty much there against Firpo.” His loss to Sharkey and Basque contender Paolina Uzcudun in 1927 ended his chances for a title shot. In particular, his loss to Sharkey gave white promoters an excuse to end Wills’ quest for the title. His narrow victory over Firpo merely confirmed in the minds of white writers and boxing analysts that Wills did not really deserve a chance at either Tunney or Dempsey. Grantland Rice summed up most reporters’ attitudes when he wrote about Wills after the Firpo fight, “Wills is not a fighter in Dempsey’s class, not even close.” (Roger Kahn pointed out in his biography on Jack Dempsey that Tex Rickard had many of the nation’s sport writers on his payroll. They merely echoed his thoughts about Wills’ inferiority as a boxer.)

While Dempsey never feared Wills, his managers did. Kevin Smith declared, “Many of the men who ran boxing thought that if Dempsey and Wills fought the latter would win and that is why the bout never took place. Wills was too much of a threat.” Others are not as sure. Roger Kahn, Dempsey’s biographer, stated, “Harry Wills would have proved to be nothing more than another quick Dempsey knockout.”

What was lost in this debate is Harry Wills’ age. Harry Wills was six years older than Dempsey and as the 1920s began, Wills was already past 30 years of age. Many of the fights that eliminated Wills from serious competition occurred after Wills turned 35. Dempsey always had the advantage of youth on his side. Wills’ best years were already behind him, and if he proved to be an easy mark for Dempsey, his age would be the key factor. Kevin Smith summed up Wills’ dilemma when he told me that, “The fact that Harry was black is about the only reason that he did not get a title shot.”

Born

- May, 15, 1889

- New Orleans, Louisiana

Died

- December, 21, 1958

Cemetery

- Woodlawn Cemetery

- Bronx,New York