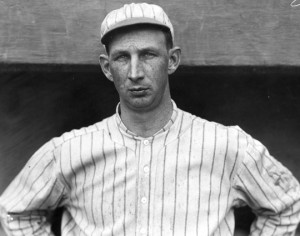

Eddie Grant (Edward Leslie Grant)

Eddie Grant

Eddie Grant was a typical Deadball Era third baseman: mediocre offensively (as attested by his lifetime .249 batting average and .295 slugging percentage) but defensively reliable, particularly against the bunt. “As a batter [Grant] was noted for his ability to sacrifice,” remembered Mike Donlin, “and he could lay back near third base and still throw out the fastest runners after they had bunted.” In his playing days “Harvard Eddie” was best known for his Ivy League diplomas. In an era when most of his teammates played poker while traveling by train, the intellectual Grant generally could be found smoking his pipe and reading a book. Today, however, he is remembered as the most prominent major leaguer killed in combat during World War I (others include one-gamers Bun Troy and Alex Burr, both of whom were killed in France within a week of Grant).

Edward Leslie Grant was born on May 21, 1883, in Franklin, Massachusetts, 30 miles south of Boston. After graduating from the public high school in 1901, Eddie spent a post-graduate year at Dean Academy in Franklin before matriculating at Harvard College in the fall of 1902. That year he distinguished himself as the freshman basketball team’s top scorer and, according to the Harvard Crimson, “a valuable team man and excellent left-handed batter” for the freshman baseball team. As a sophomore Eddie played varsity basketball and tried out for varsity baseball, but before the first game he was declared ineligible for having received money playing in an independent league the previous summer. With intercollegiate competition no longer an option, he joined his class team and spent the summer with St. Albans of Vermont’s outlaw Northern League.

Returning to Cambridge in the fall of 1904, Grant carried a heavy course load with the intention of graduating a year early and enrolling in law school. Though ambitious, Eddie was a mediocre student at Harvard, earning an average grade of slightly above C. Classmates described him as quiet, thoughtful, unassuming, and serious. In athletics, however, he stood out a bit more. Again he played class baseball-earning a spot on the 1905 All Leiter Team, Harvard’s intramural all-star team-and joined the semi-pro Milford club in Lynn, Massachusetts, as soon as school ended. That summer, in addition to fulfilling his degree requirements, Eddie got his first taste of organized baseball-at the major league level, no less. In early August the Cleveland Naps were in Boston, but Napoleon Lajoie was laid up with an infected leg. The best local substitute the Naps could find was Eddie Grant, who filled in at second base and collected three hits in his big league debut.

For the next three years Grant attended Harvard Law School during offseasons and played professional baseball during summers. While with Jersey City in 1906, his first full season in organized ball, Eddie led the Eastern League with a .322 average. That mark earned him a shot with the Philadelphia Phillies, for whom he split time with Ernie Courtney in 1907 before taking over as the regular third baseman in 1908. During the offseason of 1908-09 Grant received his law degree and was admitted to the Massachusetts bar, and for the rest of his baseball career he practiced law in Boston during the winter months.

Grant enjoyed his finest big league season in 1909, batting .269 as Philadelphia’s leadoff hitter and finishing second in the National League with 170 hits. Before a doubleheader against the New York Giants that year, he supposedly found a domino with seven white spots. As the story goes, after joking with teammates that the domino was an omen that he would have seven hits that day, Eddie went five-for-five against Christy Mathewson in the first game, then batted safely in his first two at-bats against Rube Marquard in the nightcap. The seven consecutive hits were believed to be an N.L. record, but Eddie remained modest. “I didn’t get another hit off Matty all season,” he recalled. Grant put up similar numbers for Philadelphia in 1910, when one commentator called him “perhaps the best-hitting third baseman in the National League, barring Bobby Byrne of the Pittsburgs.”

The 1910 season proved to be the apex of Grant’s career. In February 1911 he was sent to Cincinnati in the trade that brought Hans Lobert and Dode Paskert to the Phillies. For the Reds, Eddie slumped to a .223 average in his final season as a regular and improved only slightly to .239 as a part-timer in 1912. Many attributed his sudden decline to a tragedy in his personal life. Eddie had married Irene Soest in Philadelphia in 1911, but she died of heart trouble less than nine months after the wedding. The Giants purchased Grant in the midst of the 1913 season. Eddie played sparingly as New York captured its third consecutive pennant, and that fall he participated in his only World Series, appearing as a pinch-hitter and pinch-runner. He held on for two more seasons as John McGraw’s bench coach and seldom-used utilityman. Before spring training in 1916 Eddie announced his retirement, intending to devote himself to his Boston law practice. He was 32 years old.

Grant’s career as a full-time lawyer lasted barely one year. When the United States declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917, he became the first major leaguer to enlist (Hank Gowdy was the first active major leaguer). After four months of officer training in Plattsburgh, New York, Grant was commissioned as captain of Company H of the 307th Infantry Regiment and sent to Camp Upton on Long Island for several months of training with the troops he would lead. Arriving in France as part of the American Expeditionary Forces, Grant’s division saw some combat before being assigned to the Meuse-Argonne offensive, the final great American drive of the war.

On October 2, 1918, the 307th Regiment launched an attack in the Argonne Forest, a rugged, heavily wooded area with thick underbrush, deep ravines, and marshes. By the morning of the third day, October 5, Eddie Grant was exhausted. He hadn’t slept since the beginning of the offensive, and some fellow officers noticed him sitting on a stump with a cup of coffee in front of him, too weak to lift the cup. One of his troops, a former policeman at the Polo Grounds, remembered: “Eddie was dog-tired but he stepped off at the head of his outfit with no more concern than if he were walking to his old place at third base after his side had finished its turn at the bat. He staggered from weakness when he first started off, but pretty soon he was marching briskly with his head up.” Later that day the 307th was moving forward when Major Jay, as he was carried past on a litter, ordered Captain Grant, the highest-ranking officer left in his battalion, to assume command. The major had hardly spoken when a shell came through the trees, wounding two of Grant’s lieutenants. Eddie was waiving his hands and calling out for more stretcher bearers when a shell struck him. It was a direct hit, killing him instantly.

Eddie Grant was buried in the Argonne Forest, only a few yards from where he fell. Later his remains were moved to the Romagne Cemetery. A monument in Grant’s honor was unveiled at the Polo Grounds on Memorial Day 1921, and a highway in the Bronx, a baseball field at Dean Academy (now Dean Junior College), and two American Legion posts still bear his name.

Born

- May, 21, 1883

- Franklin, Massachusetts

Died

- October, 05, 1918

- Argonne Forest, France

Cause of Death

- killed in action in World War I

Cemetery

- Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery and Memorial

- Lorraine, France