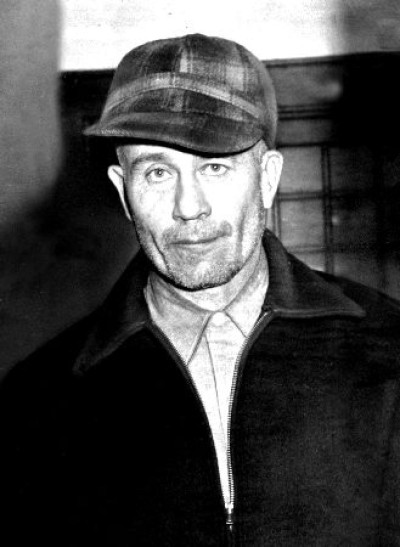

Ed Gein (Ed Gein)

Edward Theodore Gein was born in La Crosse County, Wisconsin on August 27, 1906, the second of two boys of George Philip (August 4, 1873 – April 1, 1940) and Augusta Wilhelmine (née Lehrke) Gein (July 21, 1878 – December 29, 1945), the daughter of Prussian immigrants.[citation needed] Gein had an older brother, Henry George Gein (January 17, 1901 – May 16, 1944). Augusta despised her husband, and considered him a failure for being an alcoholic who was unable to keep a job; he had worked at various times as a carpenter, tanner, and insurance salesman. Augusta owned a local grocery shop and sold the location in 1914 for a farm to purposely live in isolation near Plainfield, Wisconsin, which became the Gein family’s permanent residence.

Augusta took advantage of the farm’s isolation by turning away outsiders from influencing her sons. Edward left the premises only to attend school. Outside of school, he spent most of his time doing chores on the farm. Augusta, a fervent Lutheran, preached to her boys about the innate immorality of the world, the evil of drinking, and the belief that all women were naturally prostitutes and instruments of the devil. She reserved time every afternoon to read to them from the Bible, usually selecting graphic verses from the Old Testament concerning death, murder, and divine retribution.

Edward was shy, and classmates and teachers remembered him as having strange mannerisms, such as seemingly random laughter, as if he were laughing at his own personal jokes. He was sometimes bullied. To make matters worse, his mother punished him whenever he tried to make friends. Despite his poor social development, he did fairly well in school, particularly in reading. While Gein was devoted to pleasing his domineering mother, Augusta was rarely pleased with her boys, believing that they were destined to become failures and alcoholics just like their father. In their teenage years and early adulthood, Henry and Ed remained detached from people outside of their farmstead, and had only each other for company.

George Philip Gein died of heart failure caused by his alcoholism on April 1, 1940, aged 66. Subsequently, Henry and Ed began doing odd jobs around town to help cover living expenses. By all accounts, both brothers were considered reliable and honest by residents of the community. While both worked as handymen, Ed also frequently babysat for neighbors. He enjoyed babysitting, seeming to relate more easily to children than adults. In 1941, Henry began dating a divorced, single mother of two, and planned on moving in with her; Henry worried about his brother’s affection for their mother, and often spoke ill of her around Ed, who responded with shock and hurt.

On May 16, 1944, Henry and Ed were burning away marsh vegetation on the property; the fire got out of control, drawing the attention of the local fire department. By the end of the day — the fire having been extinguished and the firefighters gone — Ed reported his brother missing. With lanterns and flashlights, Ed, Augusta and two deputies[citation needed] searched for Henry, whose dead body was found lying face down. Apparently he had been dead for some time, and it appeared that death was result of heart failure, since he had not been burned or injured otherwise. It was later reported, in Harold Schechter’s biography of Gein, Deviant, that Henry had bruises on his head. The police dismissed the possibility of foul play and the county coroner later officially listed asphyxiation as the cause of death. The authorities accepted the accident theory but there was no official investigation and an autopsy was not performed. Some suspected that Ed Gein killed his brother. Questioning Gein about the death of Bernice Worden in 1957, state investigator Joe Wilimovsky brought up questions about Henry’s death. Dr. George W. Arndt who studied the case wrote that, in retrospect, it was “possible and likely” that Henry’s death was “the “Cain and Abel” aspect of this case”.

Gein and his mother were now alone. Augusta suffered a paralyzing stroke shortly after Henry’s death, and Gein devoted himself to taking care of her. Sometime in 1945, Gein later recounted, he and his mother visited a man named Smith who lived nearby to purchase straw. According to Gein, Augusta witnessed Smith beating a dog. A woman inside the Smith home came outside and yelled to stop. Smith beat the dog to death. Augusta was extremely upset by this scene. What bothered her did not appear to be the brutality toward the dog but the presence of the woman. Augusta told Ed that the woman was not married to Smith and so had no business being there. “Smith’s harlot,” Augusta angrily called her. She suffered a second stroke soon after, and her health deteriorated rapidly. She died on December 29, 1945, at the age of 67. Ed was devastated by her death; in the words of author Harold Schechter, he had “lost his only friend and one true love. And he was absolutely alone in the world.”

On November 16, 1957, Plainfield hardware store owner Bernice Worden disappeared, and police had reason to suspect Gein. Worden’s son told investigators that Gein had been in the store the evening before the disappearance, saying he would return the next morning for a gallon of anti-freeze. A sales slip for a gallon of anti-freeze was the last receipt written by Worden on the morning she disappeared. Upon searching Gein’s property, investigators discovered Worden’s decapitated body in a shed, hung upside down by ropes at her wrists, with a crossbar at her ankles. The torso was “dressed out like a deer”. She had been shot with a .22-caliber rifle, and the mutilations were made after her death.

Searching the house, authorities found:

Whole human bones and fragments

Wastebasket made of human skin

Human skin covering several chair seats

Skulls on his bedposts

Female skulls, some with the tops sawn off

Bowls made from human skulls

A corset made from a female torso skinned from shoulders to waist

Leggings made from human leg skin

Masks made from the skin from female heads

Mary Hogan’s face mask in a paper bag

Mary Hogan’s skull in a box

Bernice Worden’s entire head in a burlap sack

Bernice Worden’s heart “in a plastic bag in front of Gein’s potbellied stove”

Nine vulvae in a shoe box

A young girl’s dress and “the vulvas of two females judged to have been about fifteen years old”

A belt made from female human nipples

Four noses

A pair of lips on a window shade drawstring

A lampshade made from the skin of a human face

Fingernails from female fingers

These artifacts were photographed at the state crime laboratory and then destroyed.

When questioned, Gein told investigators that between 1947 and 1952, he made as many as 40 nocturnal visits to three local graveyards to exhume recently buried bodies while he was in a “daze-like” state. On about 30 of those visits, he said he came out of the daze while in the cemetery, left the grave in good order, and returned home emptyhanded. On the other occasions, he dug up the graves of recently buried middle-aged women he thought resembled his mother and took the bodies home, where he tanned their skins to make his paraphernalia.

Gein admitted robbing nine graves, leading investigators to their locations. Because authorities were uncertain as to whether the slight Gein was capable of single-handedly digging up a grave during a single evening, they exhumed two of the graves and found them empty (one had a crowbar in place of the body), thus apparently corroborating Gein’s confession. Allan Wilimovsky of the state crime laboratory participated with opening three test graves identified by Gein. The caskets were inside wooden boxes; the top boards ran crossways (not lengthwise). The tops of the boxes were about two feet below the surface in sandy soil. Gein had robbed the graves soon after the funerals while the graves were not completed. They were found as Gein described: One casket was empty, one Gein had failed to open when he lost his pry bar, and most of the body was gone from the third but Gein had returned rings and some body parts.

Soon after his mother’s death, Gein began to create a “woman suit” so that “…he could become his mother—to literally crawl into her skin”. Gein’s practice of donning the tanned skins of women was described as an “insane transvestite ritual.” Gein denied having sex with the bodies he exhumed, explaining: “They smelled too bad.” During state crime laboratory interrogation, Gein also admitted to the shooting death of Mary Hogan, a tavern owner missing since 1954 whose head was found in his house, but he later denied memory of details of her death.

A 16-year-old youth, whose parents were friends of Gein and who attended ball games and movies with him, reported that Gein kept shrunken heads in his house, which Gein had described as relics from the Philippines, sent by a cousin who had served on the islands during World War II. Upon investigation by the police, these were determined to be human facial skins, carefully peeled from corpses and used by Gein as masks. Waushara County sheriff Art Schley reportedly assaulted Gein during questioning by banging Gein’s head and face into a brick wall. As a result, Gein’s initial confession was ruled inadmissible. Schley died of heart failure in 1968, at age 43, before Gein’s trial. Many who knew Schley said he was traumatized by the horror of Gein’s crimes and this, along with the fear of having to testify (especially about assaulting Gein), caused his death. One of his friends said: “He was a victim of Ed Gein as surely as if he had butchered him.”

On November 21, 1957, Gein was arraigned on one count of first degree murder in Waushara County Court, where he pled not guilty by reason of insanity. Found mentally incompetent and thus unfit for trial, Gein was sent to the Central State Hospital for the Criminally Insane (now the Dodge Correctional Institution), a maximum-security facility in Waupun, Wisconsin, and later transferred to the Mendota State Hospital in Madison, Wisconsin. He was diagnosed with schizophrenia.

In 1968, Gein’s doctors determined he was sane enough to stand trial. The trial began on November 14, 1968, lasting one week. He was found guilty of first-degree murder by Judge Robert H. Gollmar, but because he was found to be legally insane, he spent the rest of his life in a mental hospital. “Due to prohibitive costs,” Judge Gollmar wrote, “Gein was tried for only one murder—that of Mrs. Worden.”

Gein’s house and property were scheduled to be auctioned March 30, 1958, amid rumors the house was to become a tourist attraction. On March 27, the house was destroyed by fire. Arson was suspected, but the cause of the blaze was never officially solved. When Gein learned of the incident while in detention, he shrugged and said, “Just as well.” Gein’s car, which he used to haul the bodies of his victims, was sold at public auction for $760 to carnival sideshow operator Bunny Gibbons. Gibbons later charged carnival goers 25¢ admission to see it.

On July 26, 1984, Gein died of respiratory failure due to lung cancer at the age of 77 in Stovall Hall at the Mendota Mental Health Institute. His grave site in the Plainfield Cemetery was frequently vandalized over the years; souvenir seekers chipped off pieces of his gravestone before the bulk of it was stolen in 2000. The gravestone was recovered in June 2001 near Seattle and is now in storage at the Waushara County Sheriff’s Department.

Born

- August, 27, 1906

- USA

- La Crosse County, Wisconsin

Died

- July, 26, 1984

- USA

- Madison, Wisconsin

Cemetery

- Plainfield Cemetery

- Plainfield, Wisconsin

- USA