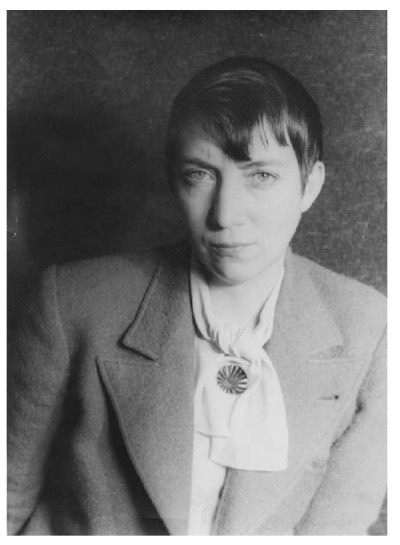

Berenice Abbott (Berenice Abbott)

Abbott was born in Springfield, Ohio and brought up there by her divorced mother. She attended the Ohio State University, but left in early 1918. In 1918 she moved with friends from OSU to New York’s Greenwich Village, where she was ‘adopted’ by the anarchist Hippolyte Havel. She shared an apartment on Greenwich Avenue with several others, including the writer Djuna Barnes, philosopher Kenneth Burke, and literary critic Malcolm Cowley. At first she pursued journalism, but soon became interested in theater and sculpture. In 1919 she nearly died in the influenza pandemic. Abbott went to Europe in 1921, spending two years studying sculpture in Paris and Berlin. She studied at the Académie de la Grande Chaumiere in Paris and the Kunstschule in Berlin. During this time, she adopted the French spelling of her first name, “Berenice,” at the suggestion of Djuna Barnes. In addition to her work in the visual arts, Abbott published poetry in the experimental literary journal transition. Abbott first became involved with photography in 1923, when Man Ray hired her as a darkroom assistant at his portrait studio in Montparnasse. Later she wrote: “I took to photography like a duck to water. I never wanted to do anything else.” Ray was impressed by her darkroom work and allowed her to use his studio to take her own photographs. In 1926, she exhibited her work in the gallery “Au Sacre du Printemps” and started her own studio on the rue du Bac. After a short time studying photography in Berlin, she returned to Paris in 1927 and started a second studio, on the rue Servandoni.

Abbott’s subjects were people in the artistic and literary worlds, including French nationals (Jean Cocteau), expatriates (James Joyce), and others just passing through the city. According to Sylvia Beach, “To be ‘done’ by Man Ray or Berenice Abbott meant you rated as somebody”. Abbott’s work was exhibited with that of Man Ray, André Kertész, and others in Paris, in the “Salon de l’Escalier” (more formally, the Premier Salon Indépendant de la Photographie), and on the staircase of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. Her portraiture was unusual within exhibitions of modernist photography held in 1928–9 in Brussels and Germany. In 1925, Man Ray introduced her to Eugène Atget’s photographs. She became interested in Atget’s work, and managed to persuade him to sit for a portrait in 1927. He died shortly thereafter. While the government acquired much of Atget’s archive — Atget had sold 2,621 negatives in 1920, and his friend and executor André Calmettes sold 2,000 more immediately after his death — Abbott was able to buy the remainder in June 1928, and quickly started work on its promotion. An early tangible result was the 1930 book Atget, photographe de Paris, in which she is described as photo editor. Abbott’s work on Atget’s behalf would continue until her sale of the archive to the Museum of Modern Art in 1968. In addition to her book The World of Atget (1964), she provided the photographs for A Vision of Paris (1963), published a portfolio, Twenty Photographs, and wrote essays. Her sustained efforts helped Atget gain international recognition.

In early 1929, Abbott visited New York City, ostensibly to find an American publisher for Atget’s photographs. Upon seeing the city again, however, Abbott immediately saw its photographic potential. Accordingly, she went back to Paris, closed up her studio, and returned to New York in September. Her first photographs of the city were taken with a hand-held Kurt-Bentzin camera, but soon she acquired a Century Universal camera which produced 8 x 10 inch negatives. Using this large format camera, Abbott photographed New York City with the diligence and attention to detail she had so admired in Eugène Atget. Her work has provided a historical chronicle of many now-destroyed buildings and neighborhoods of Manhattan.

Abbott worked on her New York project independently for six years, unable to get financial support from organizations (such as the Museum of the City of New York), foundations (such as the Guggenheim Foundation), or individuals. She supported herself with commercial work and teaching at the New School of Social Research beginning in 1933. In 1935, however, Abbott was hired by the Federal Art Project (FAP) as a project supervisor for her “Changing New York” project. She continued to take the photographs of the city, but she had assistants to help her both in the field and in the office. This arrangement allowed Abbott to devote all her time to producing, printing, and exhibiting her photographs. By the time she resigned from the FAP in 1939, she had produced 305 photographs that were then deposited at the Museum of the City of New York. Abbott’s project was primarily a sociological study embedded within modernist aesthetic practices. She sought to create a broadly inclusive collection of photographs that together suggest a vital interaction between three aspects of urban life: the diverse people of the city; the places they live, work and play; and their daily activities. It was intended to empower people by making them realize that their environment was a consequence of their collective behavior (and vice versa). Moreover, she avoided the merely pretty in favor of what she described as “fantastic” contrasts between the old and the new, and chose her camera angles and lenses to create compositions that either stabilized a subject (if she approved of it), or destabilized it (if she scorned it).

Abbott’s ideas about New York were highly influenced by Lewis Mumford’s historical writings from the early 1930s, which divided American history into a series of technological eras. Abbott, like Mumford, was particularly critical of America’s “paleotechnic era,” which, as he described it, emerged at end of the American Civil War, a development called by other historians the Second Industrial Revolution. Like Mumford, Abbott was hopeful that, through urban planning efforts (aided by her photographs), Americans would be able to wrest control of their cities from paleotechnic forces, and bring about what Mumford described as a more humane and human-scaled, “neotechnic era”. Abbott’s agreement with Mumford can be seen especially in the ways that she photographed buildings that had been constructed in the paleotechnic era—before the advent of urban planning. Most often, buildings from this era appear in Abbott’s photographs in compositions that made them look downright menacing. In 1935, Abbott moved into a Greenwich Village loft with the art critic Elizabeth McCausland, with whom she lived until McCausland’s death in 1965. McCausland was an ardent supporter of Abbott, writing several articles for the Springfield Daily Republican, as well as for Trend and New Masses (the latter under the pseudonym Elizabeth Noble). In addition, McCausland contributed the captions for the book of Abbott’s photographs entitled Changing New York which was published in 1939. In 1949, her photography book Greenwich Village Today and Yesterday was published by Harper & Brothers.

Abbott was not only a photographer, but also the founder of the “House of Photography”, created in 1947 to promote and sell some of her inventions. These included a distortion easel, which created unusual effects on images developed in a darkroom, and the telescopic lighting pole, known today by many studio photographers as an “autopole,” to which lights can be attached at any level. Owing to poor marketing, the House of Photography quickly lost money, and with the deaths of two designers, the company closed. Abbott’s style of straight photography helped her make important contributions to scientific photography. In 1958, she produced a series of photographs for a high-school physics textbook, including the cover titled Bouncing ball in diminishing arcs. Some of her work from this era was displayed at the MIT Museum in Cambridge, MA, in 2012. She spent time at MIT during the late 1950’s when she was hired to create new photographic images for the teaching of physics. The film “Berenice Abbott: A View of the 20th Century”, which showed 200 of her black and white photographs, suggests that she was a “proud proto-feminist”; someone who was ahead of her time in feminist theory. Before the film was completed she questioned, “The world doesn’t like independent women, why, I don’t know, but I don’t care.” As someone who lived alone her whole life, she put her work before her personal life. Very few details are known about her personal life. She never acknowledged her personal relationship with Jane Heath or any other women due to an unaccepting time.

Born

- July, 17, 1898

- Springfield, Ohio

Died

- December, 09, 1991

- Monson, Maine

Cemetery

- New Blanchard Cemetery

- Blanchard, Maine